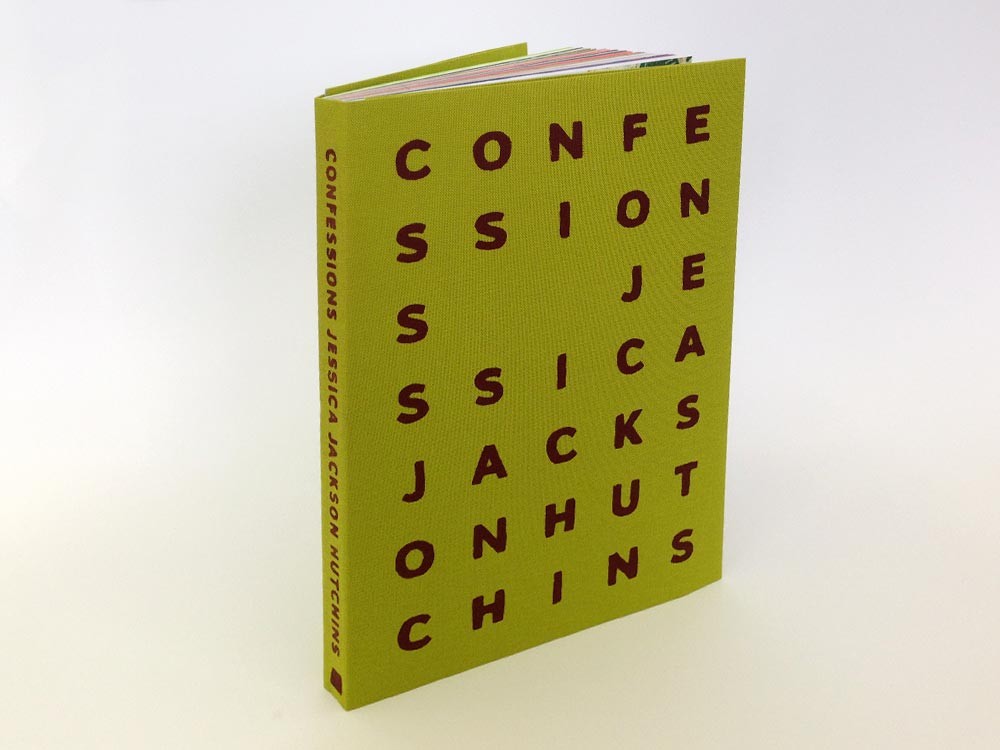

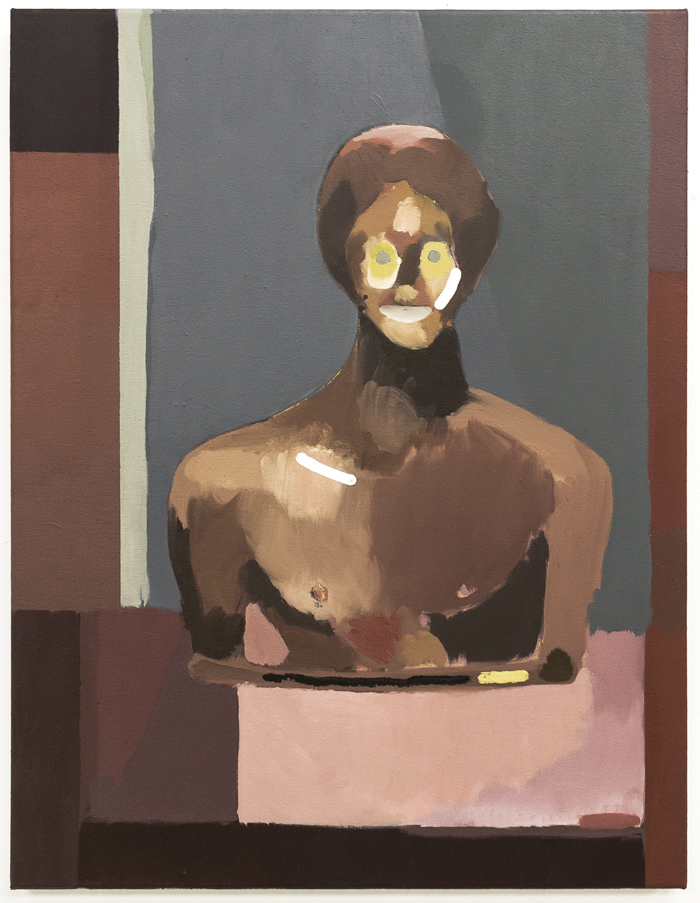

We recently caught up with Seattle-based artist, JD Banke about his current show at Nationale, THE MEANING OF LIFE IS LIVING.

Gabi Lewton-Leopold: THE MEANING OF LIFE IS LIVING, the title of your current show at Nationale, is a bold and seemingly simple affirmation that can be so difficult to heed in our daily lives. Can you talk a bit about what it means to you in relation to the work on view?

JD Banke: It's a play on words in regards to one of the still lifes in the show and the tradition of vanitas painting. I was imagining some Dutch master in some long ago time laboring for years on a masterpiece painting of fruit and a skull, and I thought it was funny that somebody would spend so much of their life making a painting about death. I try not to take art making so seriously and I thought the title should mirror the attitude of the paintings.

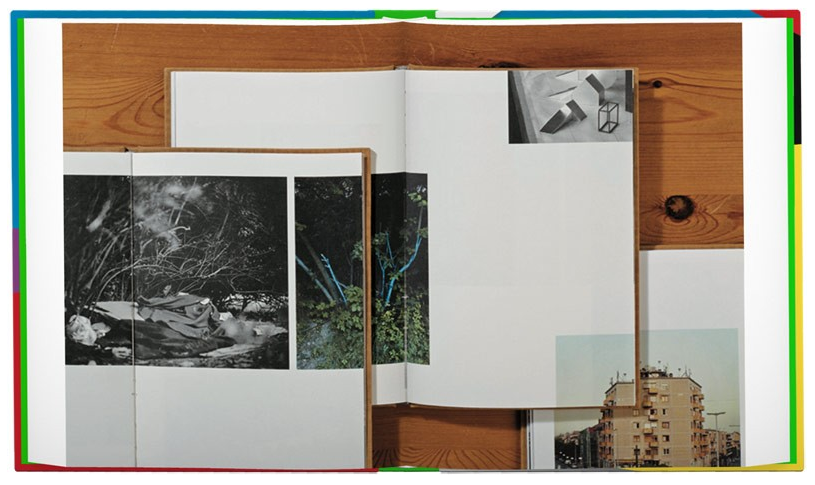

Feast for the Eyes #1, 2015, acrylic on wood, 22 x 14”

GLL: Your paintings remind us of how prevalent symbols are in our world, and how easily a simple sign can create a specific meaning. There are overt ones in your work like: logos, four leaf clover, playing cards, magic eight ball, and so forth. The symbols you use are often times also cliches or characters: Bart Simpson, Santa Claus, an abstract painting, or a human skull. There’s humor within your work partially because you use these familiar signs and mixing of “high” and “low” cultural references. Can you tell us about your interest in signs and symbols and how you view them within your work?

Feast for the Eyes #2, 2013, acrylic on wood, 38 x 48”

JDB: I'm interested in visual trends and what is cool on the Internet. I used to find joy in being a person who was using unique symbols; I found a small sense of individuality or something I could say was uniquely me. Then I came across work online that was doing similar things, and I lost that sense. I was oddly upset for awhile. I find myself thinking about originality and how it’s perceived and decided that I don't want to be original. I want to use cliche symbols and tropes to express my thoughts.

If I like a symbol visually, and can use its meaning in an odd way, I'll use it. I like the idea of having a weird visual alphabet to create with. Recently, I started including my own work into the symbol catalogue. In the Romeo and Juliet diptych they both have the word "yeah" painted on them with the colors inverted. Yeah was a painting I made in 2012, and it seemed appropriate for Romeo and Juliet to be saying that, so it’s in there.

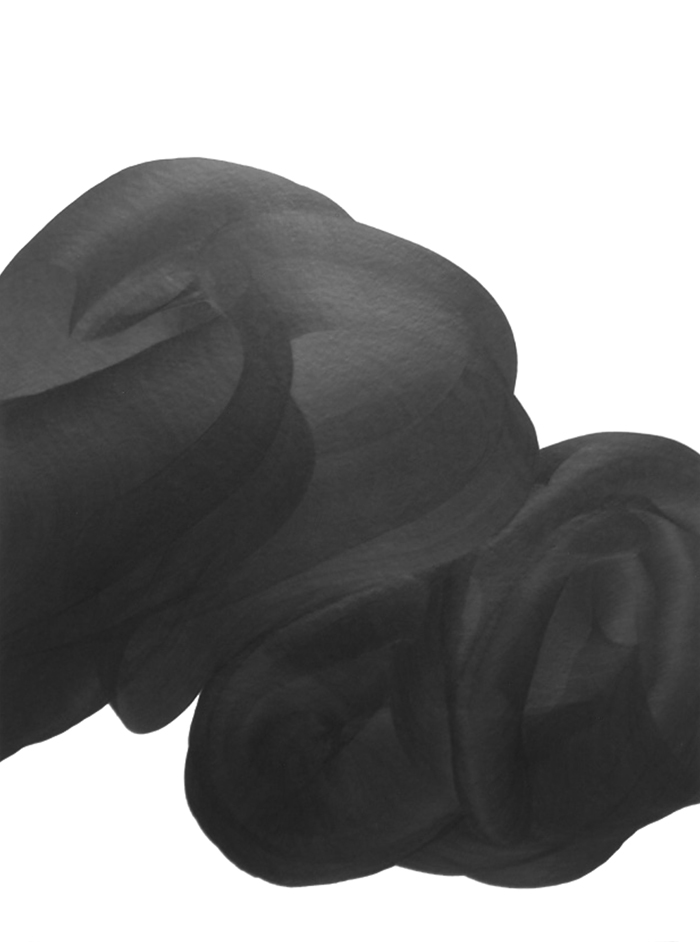

Romeo, 2015, acrylic on wood, 16.75 x 14” & Juliet, 2015, acrylic on wood, 16.75 x 14” (right)

GLL: Speaking of text, I'm interested in your practice of painting text and then redacting the words, so only fragments or the shadow of what was there remains. What does this act of erasure mean to you?

JDB: For me redacting the text can mean one of two things, or both: compositionally, if the text wasn't working and needed some blocking out of the letters to look right, I'll cross stuff out and write it again. Or, I most likely spelled something wrong and Googled the word then wrote it in correctly.

I started having ideas about writing and so I started writing down those words, and that eventually turned into poetry. I like that slow cumulative process. If I don't feel like painting, it's nice to have another medium to play with. Sometimes the writing and painting overlap and it just clicks.

GLL: Although this work is clearly influenced by the still life tradition, they also have a very object-like presence, partly because they are panels that protrude five inches from the wall, and also due to your thick application of paint. This is in contrast to the traditional still life or vanitas painting which was intended to be a “window onto the world” rather than an object itself. Is there a conscious intent to subvert boundaries between mediums by creating "sculptural" paintings?

JDB: Yes, the thickness of the panel is intended to be a subversion and blur the line between painting and sculpture. I construct my own panels, and this gives the freedom to play with space the same way a sculptor or installation artist would, but it's still painting. It's fun. This show at Nationale is the first one where none of the paintings have been on the floor.

Sure, 2015, acrylic on wood, 12 x 8” & Untitled, 2015, acrylic on wood, 19.5 x 14”

GLL: You mentioned in the past that your paintings are partly about the obligation you have to being a part of the (art) world that you’ve chosen to participate in. Can you tell us more about what you mean by “obligation” and how it informs your practice?

JDB: I feel more obligated to be aware of the art world rather than to be an active participant in it. I make references to it often, and without my awareness of it my work doesn't have as much of a context. But I like the idea of making fun of the art world because so much of it feels like a dog and pony show soap opera, which I kind of love. I see it as this weird fantasy world that I could be a part of some day if I make good paintings.

GLL: Nationale currently has your painting, Dog Stroller in the backroom gallery from your series “Chairman of the Bored.” The series features a hooded, slightly mysterious character in a camo jacket shown in various public settings: park, shopping mall, museum, and so forth. As with all of your work, it seems to represent a revolt against our homogeneous, capitalist world. Who is this character you’ve created and what is he here to tell us?

Dog Stroller, 2015, acrylic on wood, 15 x 12"

JDB: The camo guy is this weird manifestation of myself. He does things that I have done, will do or have dreamed of doing. He's trying to tell people to get a grip and chill way out.

JD Banke: THE MEANING OF LIFE IS LIVING on view at Nationale through December 31, 2015