Had to share this gorgeous photograph of represented artist Amy Bernstein, shot by Simon Metcalf in her studio. Looking forward to her upcoming two person exhibition with Patrick Kelly.

FAVE3: MAY BARRUEL

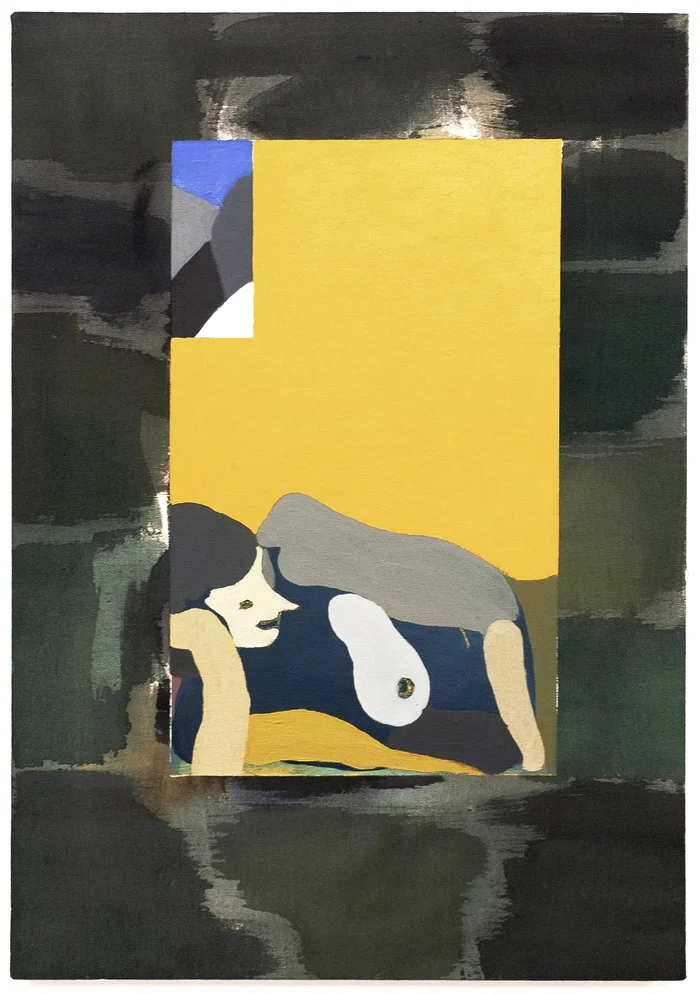

I've grown so fond of this new painting by William Matheson. I was initially surprised by the palette but the unexpected camo-like background and that pointy nose/mask have completely won me over. Or was it the boob?!

Sea of Vapors cuff by St Eloy, hand carved in wax then cast in bronze

St Eloy's fall line has arrived and I especially love all the bronze pieces, this little bracelet in particular. Plus it's named after one of the basaltic plains on the Moon, how cool is that?

Akhmatova Poems, Everyman's Library Pocket Poets

He loved three things alone:

White peacocks, evensong,

Old maps of America.

He hated children crying,

And raspberry jam with his tea,

And womanish hysteria.

… And he had married me.

1911

Need I say more?

FRONT & CENTER

We were excited to see William Matheson’s exhibition front and center on PNCA’s alumni page. Congrats, Will!

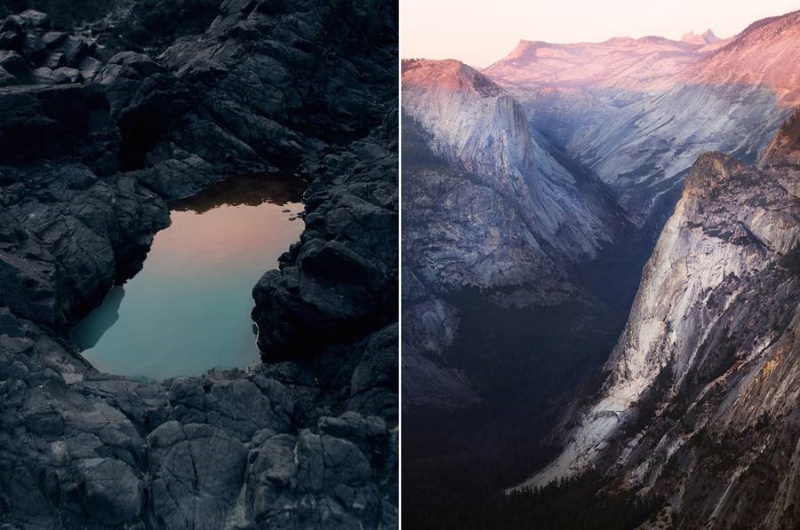

DELANEY ALLEN'S RECENT WORK

INTERVIEW: SARAH MIKENIS

The last time we saw Sarah Mikenis was at the opening reception for Everything We Ever Wanted, our summer group painting show. Soon after the opening Sarah headed off to Maine for her residency at Skowegean School of Painting & Sculpture. Now back on the West Coast, she shares some of her insights and work from her productive and eye-opening summer. Thanks for letting us in on this special place, Sarah!

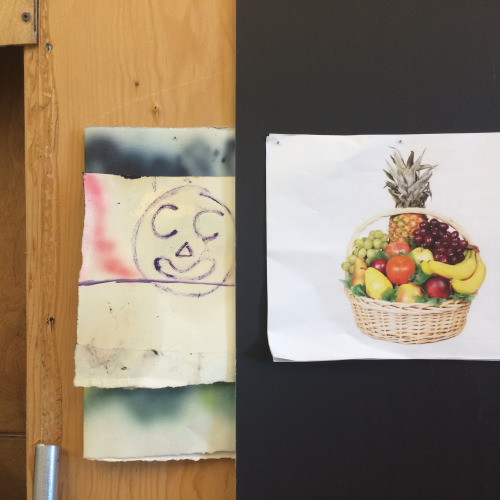

Sarah's studio at Skowgegan

Gabi Lewton-Leopold: Have you ever attended a residency program of this type before?

Sarah Mikenis: I attended a four-week residency at the Vermont Studio Center in 2011. While very different than Skowhegan, working in a new environment away from the comfort of your home and studio, meeting and working alongside talented artists from around the world, and having space and time to concentrate on your work were present in both residencies.

GLL: How were your days and evenings structured at Skowhegan?

SM: On a typical day I woke up and had breakfast sitting outside by the lake around 8:30. I made an effort to walk up the hill to upper campus and start working in my studio by 9:30. I worked in the studio in the morning until breaking for lunch on upper campus at 12:30 or 1. After lunch I might stop by the library porch and browse a book or just drink coffee and chat. Then back to the studio to work for the rest of the afternoon. Everyone on campus had some job during the summer, so two afternoons a week I worked in the fresco workshop cleaning tools, mixing plaster or pigments, or helping prepare the walls in the fresco barn for new large paintings. Also, once a week for five of the nine weeks we had individual studio visits with one of the resident faculty members.

Dinner was down the hill by the lake at 6. After dinner was dependent on the day: I might spend the evening in the library relaxing and reading books, watch a DVD in my room, or head back up to the studio to work late. There were a lot of evenings spent hanging out and drinking beer in the Common House. Some nights there might be video screenings in the Fresco Barn, and Friday nights were lectures by visiting or resident faculty artists. Saturday nights there was usually a dance party, and other evenings there might be a special event like a Red Farm dinner with a visiting artist or an opening with wine and cheese in the Fresco Barn.

GLL: What was your most challenging moment/time during the program?

SM: I think the most challenging part of the residency might have been the lack of solitude for me. There are challenges to being out of your comfort zone, away from your family, your partner, your apartment, your studio, and your usual way of doing things. But as an introverted person, being thrown in the middle of 65 participants plus faculty and staff for every meal and every event, and having a roommate for the first time since college, was certainly challenging. Of course that feeling of being slightly uncomfortable and being constantly surrounded by artists is what creates this amazing, buzzing, vibrant environment and makes the entire experience of being at Skowhegan what it is, and I find myself really missing all those interactions and exchanges now that I’m home.

Last Month's It Girl, 2015 oil, spray-paint, acrylic, and Flashe on canvas, 66 x 40"

GLL: Now your most rewarding/exhilarating….

SM: By far the most rewarding part of the experience was the friendships that I formed and the truly incredible generosity of everyone that I met. Generosity is a word that I continue to come back to again and again when I reflect on my time there. I found it in many forms, from people being so generous with their time, energy and ideas in studio visits, to the commitment of the resident faculty to the participants, to my roommate and friends going out of their way for me with acts of kindness when I was dealing with some personal things while there.

GLL: What was a surprising/unexpected aspect of the experience?

SM: I wasn’t expecting to find such a heartfelt emphasis on community while I was there. The individual artist and focus on making work were of course extremely important, but building relationships and seeing the class as being part of a continued support group for each other became an essential part of the experience.

GLL: Did the time and environment lend itself well towards experimentation within your practice? If so, how did your work change?

SM: I think working in a new studio, in a new environment with new people inherently changes your ability to approach your work in a different way. Plus, having all day to work without worrying about school or work or cooking or cleaning just simply allows the time and space to think and physically work through more ideas than is possible while in school.

When I got to Skowhegan I knew I wanted to get working right away, whether or not I had the perfect idea of what to get started on. I had a vague idea that I wanted to make abstract paintings that looked like purses. The result was three pieces that ranged in their representation of purses from quite literal to much more abstract, but all of the pieces took my work in a direction that became more sculptural and object-like than any work I had made before. Suddenly I was finding ways to bend, fold, braid and cut canvas into different shapes, and play with the materiality of paint to create surfaces that felt like leather, metal or paper.

Leaving the constraint of the “purse” and thinking more broadly about fashion, the construction of garments, and the conventions of painting, I made three more works that continued to explore a tension between painting and sculpture. I felt really free and excited about ways that I could cut, fold, and reattach the canvas to itself, make a painting that looked wrinkled, or a painting that was bulging and stuffed. The paintings that I showed at Nationale in June in Everything We Ever Wanted were still lifes painted from objects I constructed out of foam, papier-mâché, fabric, and paint. I feel like I’ve come full circle in the past year in some way as the paintings themselves have become more like constructed objects that also still play with illusionistic space.

Untitled, 2015, oil spray paint, Flashe on canvas, 44 x 30”

Pink, Red, Wrinkled, and Stuffed, 2015, oil on canvas, 60 x 50”

GLL: Can you tell us more about your interactions with the other artists? Did you find some kindred spirits and what was their work like?

SM: Interaction between artists was happening all the time, whether it was conversations at dinner, talking on the library porch, or impromptu studio visits with one another. We also had other more structured time to talk to each other about our work. I mentioned that we had weekly individual studio visits with resident faculty, and we also met with one of the visiting artists for an individual studio visit. Twice during the residency, at week four and at the end of the summer, there were open studio days to walk around campus and see everyone’s work. Halfway through the summer the painters began a Painting Happy Hour as a good excuse to have a cocktail before dinner and exchange group studio visits. We also began another small informal group that exchanged studio visits centered on our shared interest in fashion and the various ways fashion informed our work. Resident faculty Sarah Oppenheimer’s partner Noga Shalev is a clothing designer, so we had the opportunity to see her studio as well as take part in a fashion shoot with some of her newest designs.

There was an incredible diversity of practices among the residents. During the first week we had a marathon slide show where all 65 participants presented their work. I remember sitting in the Fresco Barn, being so blown away during those slide talks at the talent and intelligence gathered together in one place for nine weeks. That being said, there were several artists that I shared particular affinities with for various reasons, three being Sophie Grant, Linnea Rygaard, and Anna Queen.

Sophie Grant recently finished her MFA at Hunter and lives in Brooklyn, New York. Sophie is an abstract painter, and although her work is different from mine I found we shared a lot in common dealing with creating tension between illusion and collage. Sophie is really masterful at playing with and confusing what parts of the painting are painted, what parts are collage, what is cut out or what is behind versus in front. We shared an interest in color and pushing our palettes to be a little bit “wrong” in some way. We really enjoyed sharing thoughts on how we thought about materiality of paint and application of paint. Sophie is currently working with pours and staining and creating shimmery surfaces. She was also experimenting with creating shaped canvases while at Skowhegan, and taking the canvas off of stretcher bars completely to explore hanging and draping the canvas in different ways.

Linnea Rygaard is from Sweden, and makes larger than life abstract paintings heavily influenced by architectural spaces. Her paintings work with perspective and pushing perspective in ways that created at times a believable, but also impossible space. Her work also plays with design and pattern, although in different ways than I work with pattern, and the paintings oscillate between tight, rigid, almost trompe l’oeil areas to really loose, luscious, painterly applications of paint.

Anna Queen graduated from MICA and currently lives in Maine. Anna’s work incorporates found materials; mostly building materials found in hardware stores, as well as ceramics and fabricated pieces. I was particularly drawn to the way Anna utilized light, reflections, and transparency, and combinations of colors in her work. She played with arrangements of materials as well as expectations of materials and gravity, like making cast concrete appear as if it were crinkled paper.

GLL: Did the experience change the way you think about community and studio practice?

SM: The support and encouragement at Skowhegan really reinvigorated my belief in the importance of community among artists. There is a built in community in grad school that is really comfortable, but Skowhegan felt like a call to action for getting outside of that school group and finding ways to build community at home in Eugene and Portland. It definitely poses a question for myself about how I can reach out and develop relationships around me, what are other ways to interact besides gallery openings and artist talks, and how can I be more generous with my time and energy?

Also, since we’re talking about community, please take a moment to check out www.skow2015forlife.com. Upon returning home after the residency, Jeff Prokash, a fellow participant, learned that during his absence his brother, Tim, was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. Participants, faculty, and staff have donated work on this site that is available for purchase to help the Prokash family and Tim’s treatment.

Untitled, 2015, oil, acrylic, and Flashe on canvas, 43 x 56”

GLL: What was your favorite thing to do on your “down time”?

SM: On a beautiful, hot day there was nothing better then walking a couple steps from my cottage to the lake, swimming out to the dock and lying there for an hour or two. Also, sitting on the library porch, drinking wine by the lake after dinner, doing yoga on the sun porch in my cabin, and Saturday night dance parties.

GLL: Maine: Give us three words that describe that place for you.

SM: Fireflies. Loon calls. Space.

Lake Wesserunsett at sunrise

GLL: As you move forward with your last year of grad school, what parts of your experience at Skowhegan do you take with you? What lessons/mantras/ideas are in the forefront of your mind?

SM: There is a weird pressure lurking in the back of my mind right now that this is my thesis year in grad school so it is time to really buckle down and make work I “understand” or “good” paintings for my show. I think one of the most important lessons I will be holding onto this year is embracing that feeling of not knowing, of being slightly uncomfortable, of not fully understanding something while I’m making it. I remember a conversation with my roommate, talking about how some of the paintings I was making felt really dumb and ugly, and she very wisely reminded me that those dumb, ugly things, the things we fear, or are really unsure of, are probably the best things happening in the studio.

OPENING RECEPTION FOR WILLIAM MATHESON TOMORROW 2–5 PM

So happy to be working with William Matheson again. Please join us this Sunday, September 20, for his opening reception. The new paintings are fabulous...

Bisected, flattened, bleached, pre-dyed. In an examination of the artist's absolute vision, the pretreated canvases on view for William Matheson’s second solo exhibition at Nationale, Night Was Already in My Hands, are active screens with which his brushstrokes must learn to either coexist or compete. Upon this amorphous foundation, he accordingly layers lazy geometric forms and monochromatic figures with a measured obtuseness. Certain images tantalize as perhaps Freudian dreamscapes- what does the lemon mean? Is it a house? Who are those witchy apparitions? The historical significance of Grecian and Etruscan busts are likewise questioned and reinterpreted through their appropriation as softened portraits, accented with curves of opaque color.

Inspired by the poetry of the Japanese modernist Sagawa Chika, from whom the exhibition borrows its title, Matheson explores his uncertainty towards the pressures of image production and studio practice with a lyrical sensitivity. Painting becomes an exploit of both austerity and accommodation that, in its limitations, uncovers new emotional currents.

BIO

Originally from Los Angeles, William Matheson is currently pursuing his MFA at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. He received his BFA from Portland’s Pacific Northwest College of Art in 2013. He has exhibited nationally, including a 2014 solo show, Sunless, at Nationale. Matheson is the recipient of the Milton and Sally Avery Fellowship Award from the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson, VT and a Canserrat Residency Artist Fellowship. His second solo exhibition at Nationale coincides with the announcement of his representation by the gallery.

On view September 16–October 19, 2015

Opening reception Sunday, September 20 (2–5 p.m.)

AMY BERNSTEIN, EMILY COUNTS, AND WILLIAM MATHESON JOIN NATIONALE

Nationale is pleased to announce the addition of three artists to the gallery: Amy Bernstein, Emily Counts, and William Matheson. We’ve had the pleasure of working with all three on solo shows in the past, and we are thrilled to have them join our roster of represented artists. Through their diverse styles and voices, Amy, Emily, and William bring their unique perspectives to the gallery. We look forward to many upcoming projects and exhibitions with the three of them.

BIOS

Amy Bernstein is a Portland-based artist and writer originally from Atlanta, GA. She received her BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design in 2004. Her work has been exhibited at such local spaces as the Littman Gallery at Portland State University, Car Hole Gallery, Carl & Sloan, and Worksound. Her last solo exhibition at Nationale, Notes, took place in 2014. She has received grants from the Regional Arts and Culture Council in 2012 and from Creative Capital and the Warhol Foundation in 2010. Amy will be showing at Nationale with Patrick Kelly this fall.

Emily Counts was born in Seattle, WA, and currently lives and works in Portland, OR. She studied at the Hochschule der Kunste in Berlin and the California College of the Arts, where she received her BFA. Counts was an artist in residence creating work for associated solo exhibitions at Raid Projects in Los Angeles in 2004 and Plane Space in New York in 2008. She has exhibited at the Torrance Art Museum (Torrance, CA), Garboushian Gallery (Beverly Hills, CA), Disjecta (Portland, OR), Nisus Gallery (Portland, OR), Mark Moore Gallery (Santa Monica, CA), and in Tokyo at Eitoeiko Gallery and Gallery Lara. In 2012 she received grants from both the Oregon Arts Commission and The Ford Family Foundation. She is currently a member of the Los Angeles based artist collective Durden and Ray. She had her first solo exhibition with Nationale, The Ins and Outs, in April 2015.

Originally from Los Angeles, William Matheson currently lives in Richmond, VA where he is pursuing his MFA at Virginia Commonwealth University. He received his BFA from the Pacific Northwest College of Art in 2013. He has exhibited nationally, including a 2014 solo show, Sunless, at Nationale. Matheson is the recipient of the Milton and Sally Avery Fellowship Award from the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson, VT and the Canserrat Residency Artist Fellowship. His second solo show at Nationale opens September 16, 2015.

SNEAK PEEK: PATRICK KELLY

Very much looking forward our October/November two person exhibition with Patrick Kelly and Amy Bernstein. Got a couple sneak peeks from Patrick's studio this morning.

INTERVIEW: DANIEL LONG

Daniel Long shares a few insights on his current series at Nationale A Peanut in a Suit Is a Peanut Nonetheless while at his fellowship at Lighthouse Works on Fishers Island, NY. Thanks, Daniel!

Daniel’s show will be up through this coming Monday, 9.14.15.

Daniel Long, H.H., 2014, oil on panel, 38 x 50,” from the series I Hear A Symphony (2014)

Gabi Lewton-Leopold: For your 2014 series I Hear a Symphony at the Portland Museum of Modern Art (PMOMA) you directly referenced paintings spanning many years and styles. With this current series, you seem to extend and also depart from that project. How do you see the two series as connected and separate? What has changed in your thinking and your process?

Daniel Long: I see them connected as they both ride the line of collage. Both shows and for most of my work start from having a source. The images I create are re-representations, appropriating imagery. With I Hear a Symphony, I was inspired by a quote from Francis Picabia, “If another man’s work translates my dreams, his work is mine.” With the current show, I am still applying my ways of hijacking imagery and calling them my own. All my work has my clumsy hand, which adds to the image that makes it mine. For A Peanut in a Suit Is a Peanut Nonetheless, there were more ideas of collaging in that I used different sources at times to create the paintings. Also, in terms of putting images onto a surface. This show honed in on more so the technique (masking and cutting) and what I was getting the paint to do. My ideas of process was redirected. I have learned a lot by making this show in that I want my work to have an exploratory nature rather than looking executed. This was my first attempt to make paintings with such a rigorous process and I think a certain freedom was lost. I am not saying I knew exactly what I was going to be doing every move of the way, but my other work there is an immediacy that was not there in the works recently presented. I had a lot of fun making these paintings and getting them where I wanted them to be; using the airbrush gun is a whole lot of fun. I am trying to find a nice balance between this freedom but also having this intention.

Daniel Long, Concrete Turned to Stone, 2015, acrylic on panel, 48 x 35″

GLL: Can you speak a bit about your source imagery for this particular series? What is your process of collecting these visual influences?

DL: I like books with pictures. A lot of the imagery from my current show comes from an Ancient Egypt book. Another image came from a Valentine’s Day card I got at an art store. I, like most people, use the internet or Instagram for imagery, but it feel better when an image is discovered and you can hold it in front of your face. I’ve always collecting images and I have no real system. There are loose xerox’s around my studio and files upon files on my computer desktop. I was talking with my mentor and he suggest I get organized. This is something I will be working on.

A wall in Daniel's studio

Nationale: Do you view your paintings as a place to express covert meaning through symbols/iconography? For this series I’m thinking particularly about the two-headed snake in two of the works. Is this Apep, the Egyptian deity of chaos and destruction? If so, do you see his symbolism as important to the work?

Daniel Long: There are coded meanings, but primarily I want there to be multiple meanings where a viewer can put whatever associations they have onto the imagery. The two-headed snake yes is representing some kind of duality, not specifically chaos or destruction. With that image, I went to thinking about Robert Mitchum’s hand tattoos in Night of the Hunter. One says “Love” and the other says “Hate.” So, it is this thing where something cannot be or exist without the other. It isn’t important that it is coming from this Egyptian deity, but it becomes this visual language and symbol.

Daniel Long, Thirsty, 2015, acrylic and Flashe on panel, 48 x 36″

GLL: Can you talk about your relationship to painting in general? Your past work was more sculptural/installation based. How did painting become more important to you?

DL: I see all my work as paintings because that is the language I use. The sculpture, frame, or whatever it is, is in the background and I move things around as I would with paintings. So, I am using these formal elements as I would in a painting. Anne Ring Petersen speaks of this idea in her essay Painting Spaces. She describes entering a painting both visually and physically with the painting’s relation to space—not as illusion-ism but as something physical and tangible. I am still very much interested in these ideas.

GLL: Although you are working in a very old medium you are able to bring it into the present. I see this through your choice of materials (airbrush, Flashe, etc) and the process of rolling the paint and then layering on top of that base to create a different type of surface. I’m interested in that rolling action. Do you see it at all tied to the abstract expressionists and their use of house paint and non-art materials? Something very utilitarian about it…

DL: I have always used whatever materials are at hand. Because of that I have openness in my creative output. The rolling action makes this texture that I like because once dried and then airbrushed it gives this effect like it is a rubbing. It picks up whatever is around. I like this because of it being so indexical. Debris from my body, from my studio show up in my work, which to me is not a flaw but rather points to saying, I was here.

Daniel Long, Key Turned, 2015, acrylic on panel, 24 x 24″

GLL: How long have you been working with airbrush? Why were you drawn to it for this series in particular?

DL: I got the airbrush compressor and gun like 2 years ago? I bought it from a fella who needed to make rent. It was kinda busted so it was fun trying to figure out what it all would and could do. After buying a new gun it was such a surprise. My practice is fun and exciting and I am always looking for new ways of making. I do not want to ever just make oil paintings or only make airbrush paintings. I want to collide all the paints.

GLL: It seems that the airbrush softens the image, there’s a kind of blurring that happens that connects it to photography for me. Also, the way you blur some areas while bringing others into focus through the use of Flashe and acrylic is really interesting and reminds me of photography as well. Do you see any connection between your paintings and photography?

DL: The blurring of these images speak to my ideas on how I see painting as a flexible medium. I can see how photography could play a role in that my images exist in printed form. Whether a photocopy or whatever, my sources I print out to have a reference so they exist as a flatten image. There is a lot of simulacra happening in my process. Things exist, and then exist in some other form, and so on. I would say my work is more so connected to collage.

Daniel Long, The Hair Stood up on My Arm, 2015, acrylic and Flashe on panel, 48 x 36″

GLL: Did you think a lot about how the eye will see these different materials while making the work?

DL: Yes. I was interested in how my paintings painted with oil or acrylic photograph so poorly. Their presence is completely lost and it is really frustrating to see in slides and such, but then these airbrush paintings look so sharp digitally, whereas in person you have to be at a distance to have the image be tight. I became really fascinated with this flip-flop of viewing images in person vs. online.

Daniel with his exhibition, A Peanut in a Suit Is a Peanut Nonetheless

GLL: Can you talk about where the titles come from and how they add to the work? For me, their vague and poetic nature, rather than acting as an explanation, add to the mystery of the work. They keep it open.

DL: Titles are important because it is a way to set a tone. It gives the viewer permission on how to see the work. I take my titles from everywhere. I like for them to be open and non-directive. I am inspired by music lyrics I am listening to at the time, themes and language in gay culture, or anything that can give me a laugh. I like for the titles to have multiple meanings. My titles are not really coded nor an explanation, but rather it is like how Philip Guston speaks of painting. When the air arbitrary vanishes and the paint falls into place. It is when the title and painting have this harmonious vibe.

ELIZABETH MALASKA IN HOLDING SWAY AT PNCA

Congratulations to Elizabeth Malaska, whose paintings Lost Daughters (1) and Lost Daughters (3) were selected to be part of PNCA’s Holding Sway exhibition. Opening reception this First Thursday, September 3.

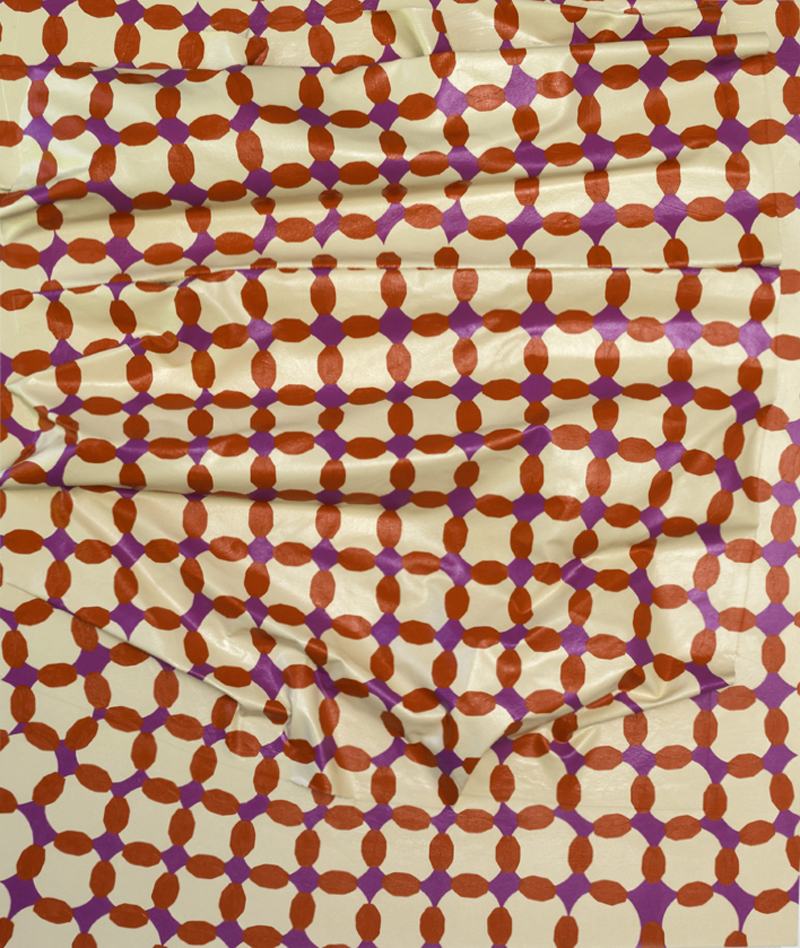

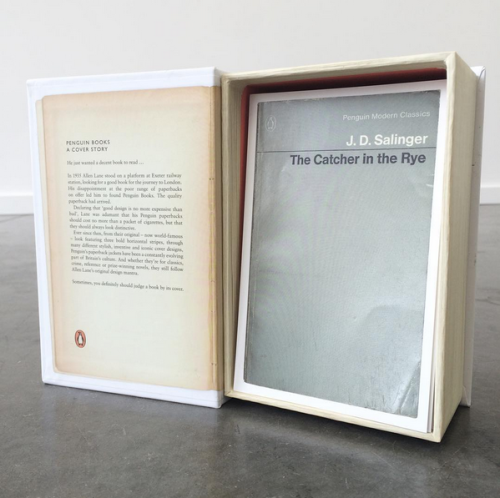

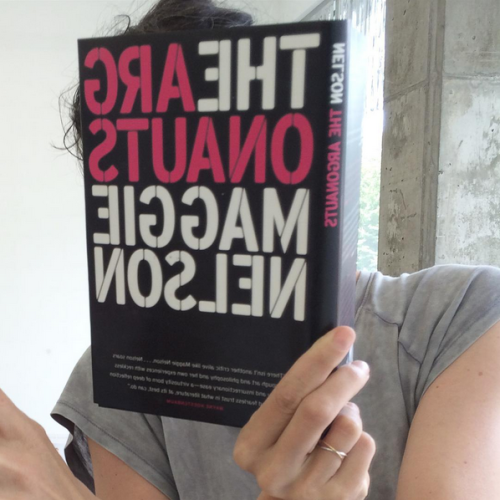

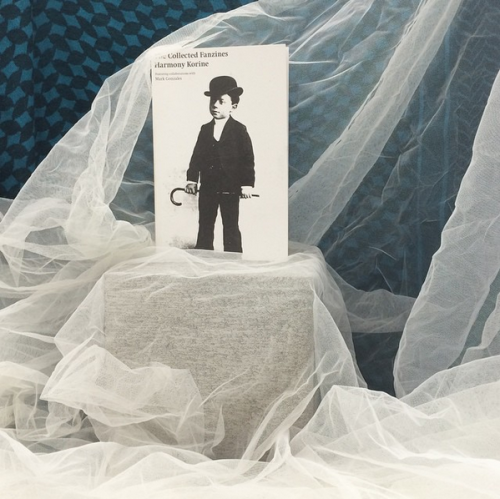

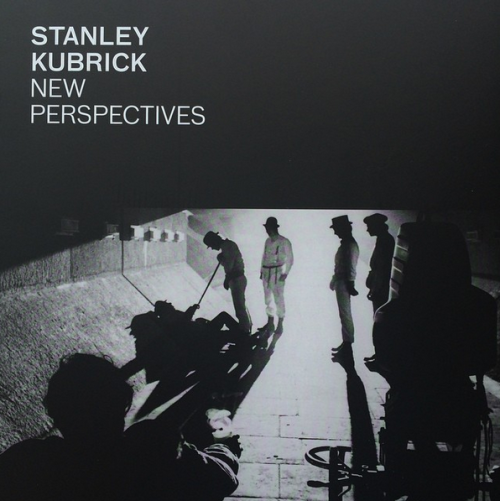

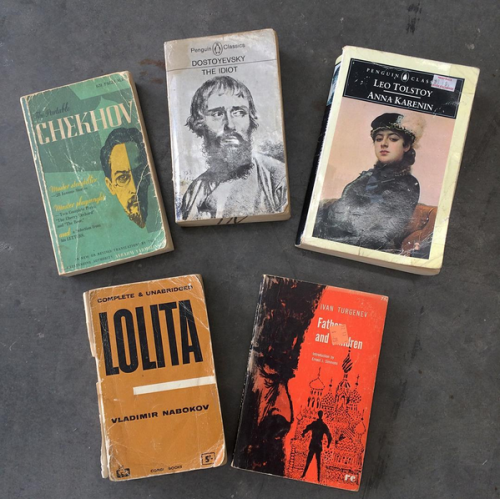

RECENT ADDITIONS TO THE SHOPS BOOKSHELVES...

Stop by and peruse all the new titles we’ve recently gotten in the shop. Good selection of used classics, too!

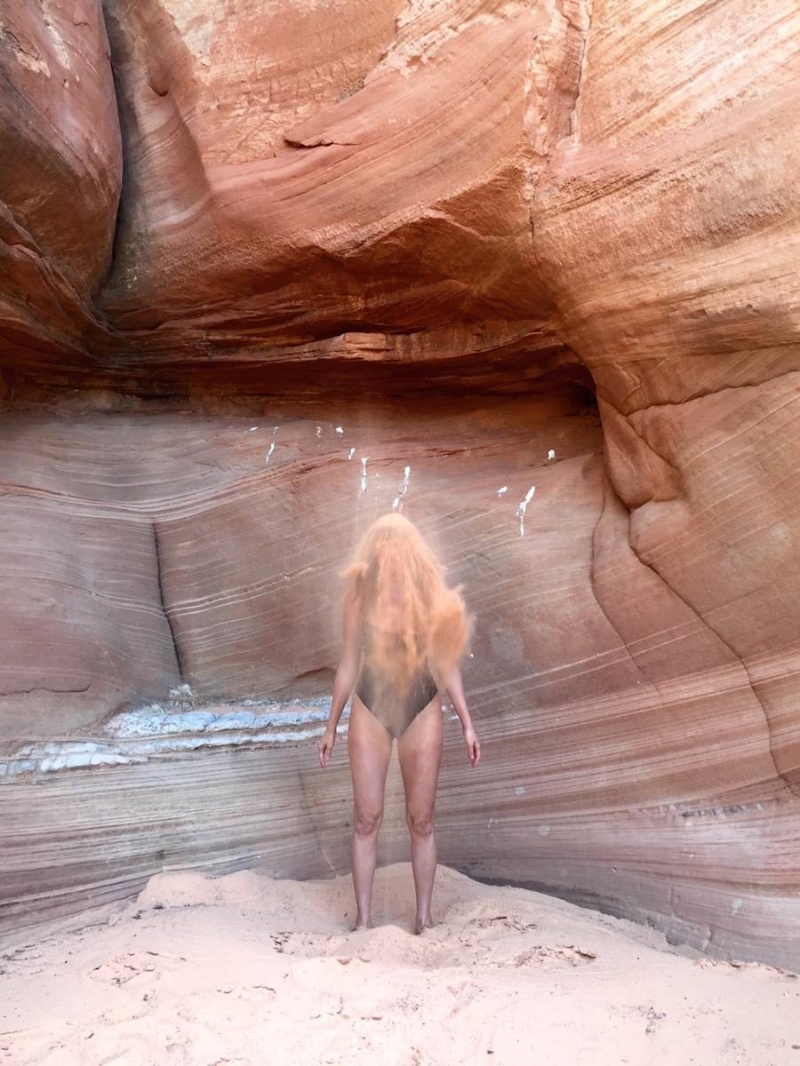

DELANEY GOES VIRAL

Today is the day Delaney Allen drives back to Portland. We’ve missed you, friend, and I can’t wait to see this photograph in person in the near future. Looks like 62756 people agree with me…

INTERVIEW : ELIZABETH MALASKA

We are pleased to introduce Nationale’s artist interview series!

Our inaugural interview is with the always fascinating, Elizabeth Malaska. Gabi Lewton-Leopold, our Assistant Director, spoke with Elizabeth recently about her ongoing series When We Dead Awaken, the first half of which she showed at Nationale in November 2014. We are looking forward to the second installment to be shown at Nationale in fall of 2016. Thanks for chatting Elizabeth!

Gabi Lewton-Leopold: Can you speak about your current series and about the next half, which you are working on now? Have you had any new insights or realizations working on the second half?

Elizabeth Malaska: Conceiving of this series, I was really inspired by thinking about the Surrealists and art as social protest and being very disturbed by domestic and foreign policy, especially the rash of shootings that were happening around that time. The Newton shooting had recently happened, which was just sort of surreal in itself. Thinking about the Surrealists and how I could respond in kind today, is what started the series. I am always looking to incorporate my love of, and how I constantly refer back to, art historical painting, looking for a way to weave that in. My work always comes from a pretty staunch feminist standpoint, so developing this idea about talking about guns and gun control and culture of violence related to guns in America gave rise to this idea of the female figure with the gun, which seemed like an interesting idea to explore, especially because it is such a stereotypical, cliché image—the bikini babe with the rifle on the calendar in the mechanic’s shop. I like things that are extreme like that because I feel like they present a pretty big challenge to take on: the pull is so strong for it to get sucked into that extreme rhetoric; can I co-opt that image and use it to my own ends?? These different threads coalesced into this idea about the post-apocalyptic scenario, and then a lot of stuff crops up along the way. I’m working on the second half now. When I started the series back in 2013 I conceived of the big paintings all at once then, and so I am working from maps or notes of pretty fleshed out paintings. It’s not like I’m stuck in time but…

GLL: So you’re saying you mapped out everything, even the ones you are working on now?

EM: Yes, but I’m also very open to things changing, it’s not like anything is set in stone for me, I’m really excited about the ideas that I came up with then and I’m excited to be making these paintings. The way that things are developing now has to do a lot with technique and the literal way that I make the paintings, the way the process of layering, the way I use materials together, the marks I make. I feel like my work has been going in a direction of greater realism and tightness, although I don’t like that word. I guess specificity, maybe like a classical technique incorporated with abstraction, I’m always going to incorporate abstraction and contemporary techniques, but in conjunction with that I’m becoming more and more interested in very traditional classical techniques and incorporating those as well, so that the range of mark making is pushed wide.

GLL: That leads to another question I had, thinking about your series before, the first show at Nationale in 2012, looking at the figures especially, they are definitely changing and becoming more classical, but you still have those architectural moments and interiors.

EM: I was looking at old work today, and I can get really caught up in technique and forget that the figure can happen in 30 minutes instead of three months. It was a reminder to not forget about that. Maybe a figure will happen where three quarters of the figure is wash and the arm is super detailed…

GLL: which is really interesting in the figure in You Will Become Me, with the blending of the two styles.

EM: Right.

GLL: You are making six more paintings?

EM: I’m working on three more large ones, two more medium sized ones, and at least half a dozen small ones. Right now I’m just working on one painting but that’s the map that exists, that I will achieve, even if I have to kill myself in the process!

You Will Become Me, 2013-2014, oil, Flashe, spray paint, charcoal, and pencil on canvas, 48 x 58 ½,” Collection of Scott Musch, Portland, OR

GLL: Can you talk a little about your process, the source imagery, and the role that drawing plays?

EM: Each size of painting happens differently. For the large paintings I definitely start with pretty detailed drawings and the source material comes from all over the place. I do a lot of image gathering and then literal collaging, and then collaging within the drawing. I like to take images out of books. I also do a lot of image research on the computer, pulling a lot of images together—sometimes I want them to work seamlessly and sometimes not seamlessly. That’s for the large ones. The medium sized ones happen way more fluidly than that. With the two medium sized ones in the last show, I did little sketches in my sketchbook, but not a really precise drawing. It’s funny, with the drawings I try to occupy this space in between knowing what I want to be there and kind of not looking at that thing very much. They (the drawings) act as some sort of defining boundary, but I don’t want to be looking at them too closely because then you just end up making a painting that looks like you are painting from source material, which isn’t interesting—just show us the source material. Using drawing to definitely create a map of the territory, but doing a lot of exploring in a lot of the un-mapped territories as I go along. The way I structure the drawing has a lot to do with mapping out areas, these areas are known and often that has a lot to do with repetition, and they are very labor-intensive, say the wood paneling on You Will Become Me, or say there will be a figure here, or there will be a vase here, or a plant here. But the way that thing happens is very determined by the process of painting itself. I have an idea about how I want that figure to stand or what I want it to look like but it’s totally open too, and those parts are always oil because it’s so much more of a plastic medium than the acrylic. It’s like these super slow labor-intensive parts and then these explosions of improvisations on a theme.

GLL: So the wood paneling is an example of the more planned out area.

EM: Yes, and it’s super repetitive. I probably spent at least two months working daily to do that, looking at reference material and also just listening to podcasts and zoning out. Like a mantra, repetition. In contrast to say the dog or the figure in that piece. The figure even more so than the dog, the figure and her firearm because her body is abstracted in some places but the gun is even more abstracted. She was painted through a processes of glazing, which happens slowly, but as the glazing came up to more of the surface things started happening quickly, body parts started moving around and getting painted out, parts were taken away and the figure went into a sort of a chaos, intentionally so. There’s a lot of control, sometimes an uncomfortable amount of control for me, I feel like I should be more loose, but it is what it is. I think I’ve had adopted this idea of a late 20th century artist being somebody that is very spontaneous and all these certain things, and part of my process through this body of work has been an acceptance of how much control, speed in terms of slowness, and technical abilities, how important those things are to me, to my work.

GLL: Have you always had that control in earlier works?

EM: No, it’s been becoming more and more important for me.

GLL: Why do you think that is?

EM: I think that I’d reached a point where I wasn’t able to communicate the point that I wanted to in a modality that was more exclusively about spontaneity and emotional responsivity. It just didn’t go as far as I wanted it to. It wasn’t as interesting as I wanted it to be.

GLL: Back to the protest idea, well, first of all I feel like, depressingly so, there’s been so much that has happened in terms of gun violence in the last couple years since you began this series.

EM: Right, and the staunch refusal by certain aspects of our society to do really anything about it.

GLL: With that in mind, do you feel that the series is at all hopeful?

EM: It has to be, although it’s not immediately apparent. I’m definitely not just a nihilist. I think that the hope is in some kind of idea of uncivilization. I’m only vaguely familiar with the philosophies of uncivilzation, but it is basically saying that the societies that we’ve created are so messed up that ultimately they need to be torn down for something else maybe more healthy for human beings on the planet to take root. So I think that there is hope for me in the female figures who possess power despite their circumstances; they are not victims and they have control. Maybe not ultimate control, but given the circumstances they possess a powerful degree of control.

GLL: And there is something hopeful in that. There is also something hopeful to me about Pause to Give Thanks That We Rise Again from Death and Live, it feels like an end and there’s something very peaceful there, although there is that darkness.

Pause to Give Thanks That We Rise Again from Death and Live, 2014, oil, Flashe, spray paint, charcoal, and pencil on canvas, 35 ½ x 32,“ Collection of Arlene Schnitzer, Portland, OR

EM: It is darkness. That’s something I’ve thought a lot about in my work, the darkness in it. I don’t see darkness as something to be afraid of, but as something that contains potential and a lot of richness. And I also think about how darkness has been associated with the feminine, and it’s interesting to me the cultural attachments we have to darkness. Part of what I am thinking about and want to explore is those stereotypes, and maybe see them in a little bit of a different light.

GLL: Can you speak a bit about your titles? Where do they come from, how do they inform the work and who is that “we” that you use so often?

EM: I love titling. Titles almost always come from stuff that I read. Poetry often. I think of painting and poetry doing really similar things, in that they are able to create worlds that talk about our world but also can point to actualities that maybe don’t exist in reality, emotional or metaphysical realities. Poetry feels like a very natural place for me to go and I really enjoy it. Titles definitely come from poetry and potential titles are things that I keep running lists of. I have pages and pages of possible titles to help myself.

GLL: So, when you are reading, a line will stick out and you’ll pull it out?

EM: Yes, something just strikes me or seems succinct in a way or talks about the body and feminism, and I know I’m going to use that at some point.

GLL: Who are some of your favorite poets?

EM: I love Diane di Prima; Michael McClure was a teacher of mine in undergrad and he was super influential. I return to the beat poets a lot, I wouldn’t say more obscure, but I’m not so into Ginsberg or Kerouac but McClure or Amiri Baraka. One of the titles in the show came from H.D. I have these great anthologies of 20th century poetry by Jerome Rothenberg and there’s just a ton of people in there, more obscure people.

GLL: And the “we?”

EM: I use the “we” to pull viewers into the narrative and I want also to implicate. What I’m trying to do is create an image that activates the viewer’s psyche and body, to some extent that is why I use the female figure. So, the “we” is a re-enforcement of that and a way to promote that.

GLL: Really a call to action, in a sense.

EM: Yes, inclusion and implication both those things, as strongly as each other.

GLL: Then there’s the “you” in You Will Become Me.

EM: You will become Me and We Have Been Naught, We Shall Be All…

GLL: Implication also carries over to the idea of protest too.

EM: Yes, that’s true.

GLL: When you talk about the Surrealists, are there any particular paintings or artists that stick out in your mind? Or, not even just Surrealists, are there any paintings in your visual bank that have stuck with you for a long time and influenced what you are doing in different ways?

EM: I looked at a lot of Surrealist works when I was doing research and starting this project. A lot of it went in one eye and came out the other. The stuff that has stuck with me was in there before—Leonora Carrington, I think about her work a lot. And I’ve been thinking about Frida Kahlo’s work more recently, too. The Surrealists are interesting too because they are a group that has been so co-opted by culture. Also, Max Ernst, I’ve always found interesting, pretty impenetrable but I’m always attracted to his work and as equally repelled by it, too. I was looking and thinking about the Analytic Cubists a lot, Juan Gris especially and Georges Braque, whom I love and whose work I think transcends Cubism. His paintings of his studio, I’ve loved those paintings since I saw them in my teens. And one in particular I want to say it’s Studio V, and there’s a big bird that’s sort of traversing across the space of his studio inexplicably, and the painting is very brown. It’s just gorgeous and I was thinking about that painting a lot when I was making Legacy of Ruin. That painting, like some Matisse paintings, has been in my psyche since I saw them 25 years ago. They are the meat and potatoes of my painter’s imagination.

Georges Braque, Studio V, 1949-50, oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 69 ½,” MoMA, NYC

Legacy of Ruin, 2014, oil, Flashe, spray paint, charcoal, and pencil on canvas, 48 x 62”

GLL: Thinking about Leonora Carrington and Frida Kahlo, they both use a lot of self-portraiture, is there a reason you steer away from that in your work, especially since you use the female figure often and it would maybe seem second nature to use yourself as the model?

EM: I do a lot of self-portraiture as a practice, just as a daily drawing practice. I feel like I’m already narcissistic enough as an artist that I don’t need to make paintings of myself. But everyone is always like, “Well, I thought that painting was of you!” but that wasn’t my intention.

GLL: Do you think that’s a product of being a female painter? That people tend to assume that?

EM: That’s interesting. I never thought about it that way, but yes of course, probably. People are just predisposed to see you as narcissistic and self-reflexive because you are a woman. But I also see it in a lot of artists’ work, that you just can’t help but put yourself into your work.

GLL: Totally different question: mentoring and teaching, do you think it has changed your own practice at all?

EM: I think it is part of what has driven me more towards technique. It shifted my gaze towards technique and once my gaze was there it was like, oh shit, there’s so much here for me to explore and use.

GLL: Do you feel that technique is always a tool that will broaden your ability versus the opposite?

EM: No, I don’t. I think it has to be used wisely. I think I can use pretty hardcore classical techniques but not get stuck in the rabbit hole of just decoration or surface, because of my foundation in the improvisational, reactionary, let’s fuck it up now approach—that’s my training and all the technique I have is stuff that I taught myself. I think it’s really hard if you get front loaded with that technique, because you get taught to be so super careful and scrutinize everything, and then it’s really hard to break out of that. But I also think it’s a really important foundation for people learning to have some technique, but I think it has to be super balanced and reserved, so that you don’t just get stuck in that because technique without the elements that bring it into the contemporary is just dead—without the chaos, or the unknown, or the uncontrollable. Like Odd Nerdrum. I guess you would say he has the contemporary in his totally disturbing subject matter, but the contemporary for me doesn’t manifest in any formal ways in his work. It doesn’t gel in the now for me, and I’m not interested in it at all, it’s just empty.

Studio photographs of Elizabeth are by Gia Goodrich.

DANIEL LONG IN MEMPHIS

Daniel Long, whose solo exhibition is currently on view at Nationale, is doing a collaborative installation for a surprise art show tonight at GLITCH in Memphis, TN…

FAVE3: ELIZABETH MALASKA

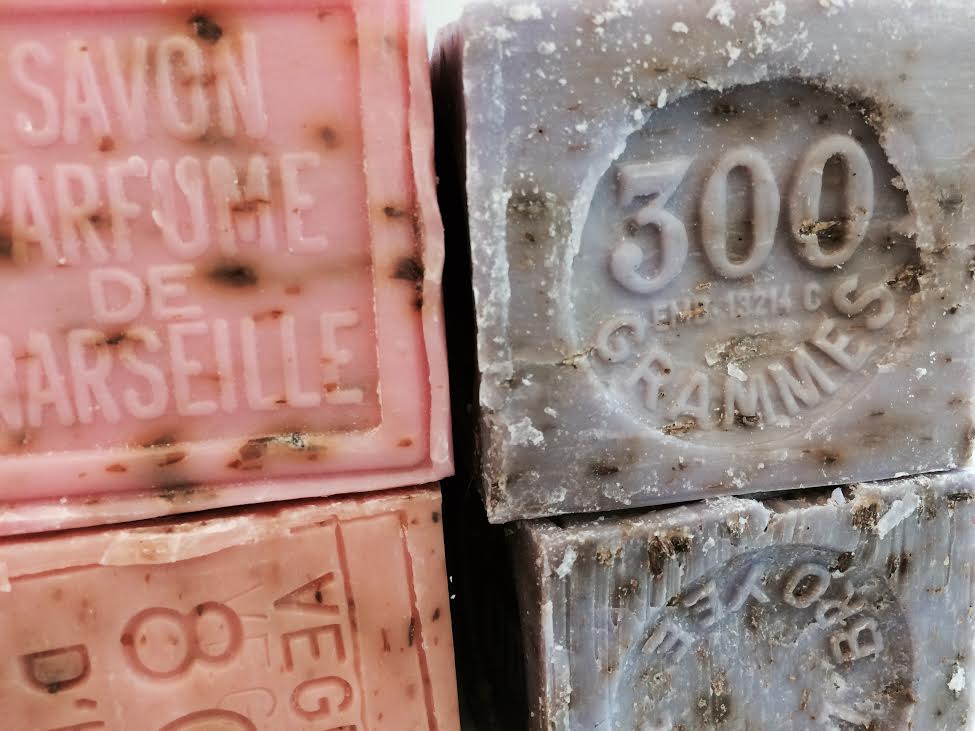

Savon de Marseille, crushed flowers soap in verbena, lavender, & rose ($12)

“LOVE LOVE LOVE this soap. Looked for it for 10 years… Lasts forever, awesome until the last sliver disappears down the drain. (Lavender all the way)."

Chloë Sevigny Written by Chloë Sevigny, Foreword by Kim Gordon, Afterword by Natasha Lyonne, Rizzoli 2015 ($35)

“I want to hate this book because it’s pure ego, but Chloe is so awesome I have to love it. Plus she’s got a pretty great ass.”

Myranda Gillies tinfoil rings cast in silver or white brass ($50-$90)

“Myranda Gillies’ tinfoil rings cast in silver are a perfect mix of low/ugly with posh. Right up my alley!”

Thanks for stopping by and sharing your favorites with us, Elizabeth!

RECENT STUDIO VISIT WITH DANIEL LONG

Gabi and I recently visited Portland painter Daniel Long in his very hot studio. So excited to see how his August solo exhibition is coming along. Save the date for his opening reception at Nationale, Sunday August 9 (2–5 p.m.). More about A Peanut in a Suit Is a Peanut Nonetheless HERE.

ELIZABETH MALASKA FEATURED ON MUSEUM

Elizabeth Malaksa was recently featured on the online art and literature journal, MUSEUM. Read about her childhood ambition, first job, and worst habit—a familiar one for many!

THE PARIS REVIEW NOW IN + SPECIAL AK INTERVIEW

Don’t miss this issue of the Paris Review, now in the shop, with our beloved Aidan Koch on the cover (+ an extensive portfolio). Couldn’t help but feature it here with some of Aidan’s sculptures–available in the backroom–from her 2013 show at Nationale, The Marble Hand.

From the Paris Review’s blog: On Aidan Koch’s cover for our Summer issue, six panels depict a woman lounging and reading and ruminating at the shore. Each panel exists both as a discrete event—here, she looks at her book; here, she shades her eyes—and as one sentence in a paragraph about the woman’s day at the beach. The issue also features Koch’s comic “Heavenly Seas,” the story of a woman who travels to a tropical location with a man she doesn’t love. It is twenty-eight pages long and contains just over a hundred words of dialogue and no narration. The difference between “Heavenly Seas” and the cover sequence is like the difference between Lydia Davis’s long short stories and her very short ones.

Koch, a native of Olympia, Washington, is the author of three book-length comics—The Whale, The Blonde Woman, and, most recently, Impressions. She also makes sculptures, ceramics, and textiles that reinterpret the classical motifs that appear in many of her comics. Her narratives are elliptical, fragmentary, and open-ended; it seemed appropriate to include “Heavenly Seas” in an issue that is largely about translation. Last month, I met Koch at her studio, in the basement of a tatty mansion she shares with eight other artists and a corn snake named Cleopatra, in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Read more HERE

FRONT AND CENTER

We were excited to see Daniel Long’s exhibition front and center on PNCA’s alumni page. Congrats, Daniel!

DANIEL LONG: INSTALL SHOTS

Thanks to everyone who attended Daniel’s reception yesterday. What a lovely afternoon we had. A Peanut in a Suit Is a Peanut Nonetheless is on view through September 14, 2015. Make sure to come see the work in person.