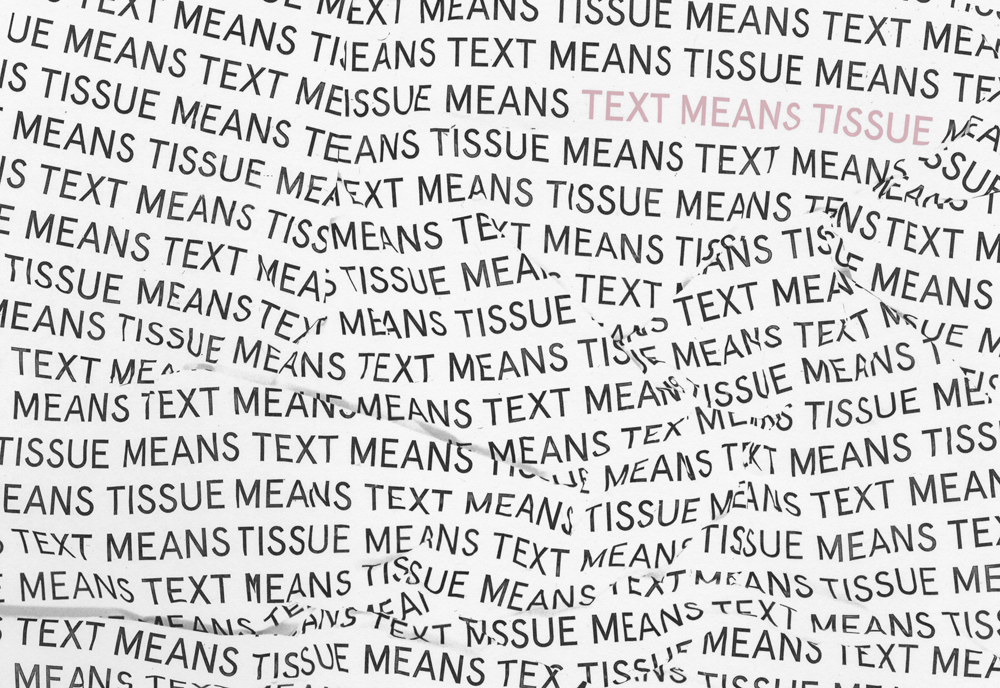

Artist, writer, and textile designer, Francesca Capone shares her thoughts on her solo show at Nationale, Text means Tissue.

Gabi Lewton-Leopold: This new body of work (exhibition and book) Text means Tissue, your 2015 project Writing in Threads, and 2012 publication Weaving Language all explore the relationship between weaving/textiles and language. When did this conversation between two seemingly disparate forms begin for you?

Francesca Capone: I started experimenting with weaving and writing during my time on the Jacquard loom at RISD. I began exploring how the repeat function of the loom could affect the metrics of the poems I was writing, and my framework for working in this way began. In 2009, I started interning and studio assisting for Jen Bervin, who has worked with text and textiles for many years, and whose thinking deeply influenced me. The more I reflect upon this question though, the more I start to convince myself that it's actually ingrained in me, as well. In the house I grew up in, my great-grandmother's ruby pink embroidered Italian alphabet sampler takes a prominent space in the kitchen. My mother makes fine leather gloves for a living—gloves, this particular garment that clothe the hands, which are so deeply emotive of language. I've found that expression through textile is actually a part of my family history, though I came to it on my own.

Francesca Capone, unsaid, unsung, unstrung (THKC), 2016, cotton and reflective thread on wood, 24 x 36"

GLL: The two most recent projects, Writing in Threads and Text means Tissue involved many collaborators—for the former, writers responded to your work and with this current series, writers responded to the question you posed about the connection between textile, language, the body, and femininity. I imagine that weaving in the studio is a solitary exercise and that making a publication with many contributors is a welcome counter. Can you talk about why collaboration is important to you?

FC: That's very true. I don't want to be a lone weaver speaking only to herself. In my experience, the best art happens in the push-pull of dialogue. I want to know what other people think, how they feel, I want to feel challenged, comforted, and inspired. I want to make work that is generous, and share the opportunities I have to create platforms for the work of others, not just my own. Collaboration always makes things more interesting, and the more I involve my community, the better the work is. I feel so fortunate to know so many talented artists and writers, and being in conversation with them drives the work I do on my loom.

Cover of Francesca's book Text means Tissue, which includes over 30 contributing writers

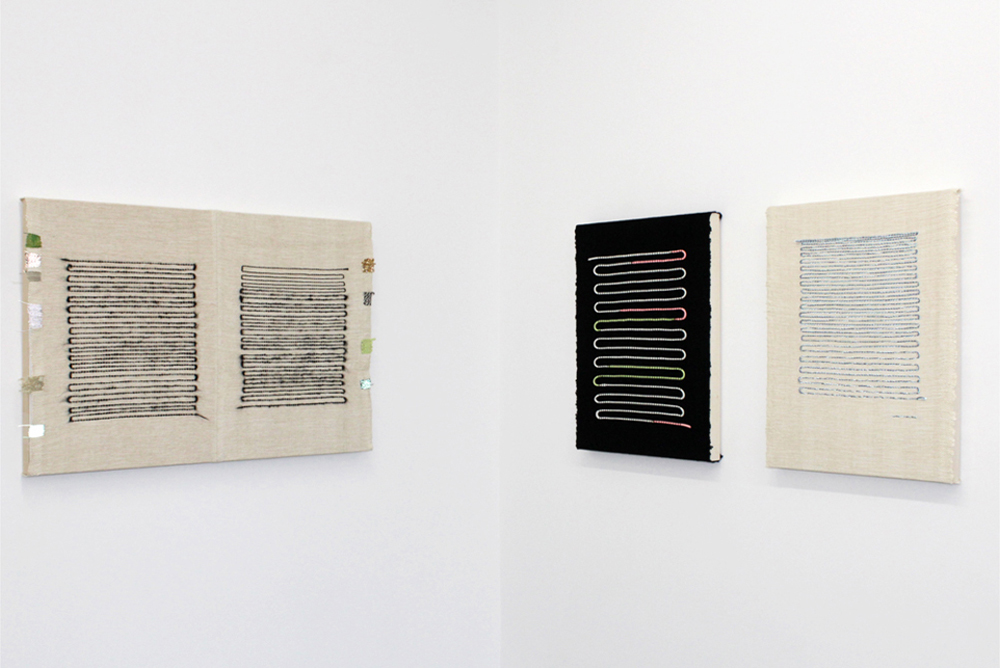

GLL: Looking back at your weavings from Writing in Threads (shown at 99c Plus Gallery in NYC), it seems that you've moved towards a more focused, pared down direction in both form and color. In Text means Tissue, you take the form of the written page as a starting point to develop your imagery. How do you see the weavings from these two series as connecting and diverging from one another?

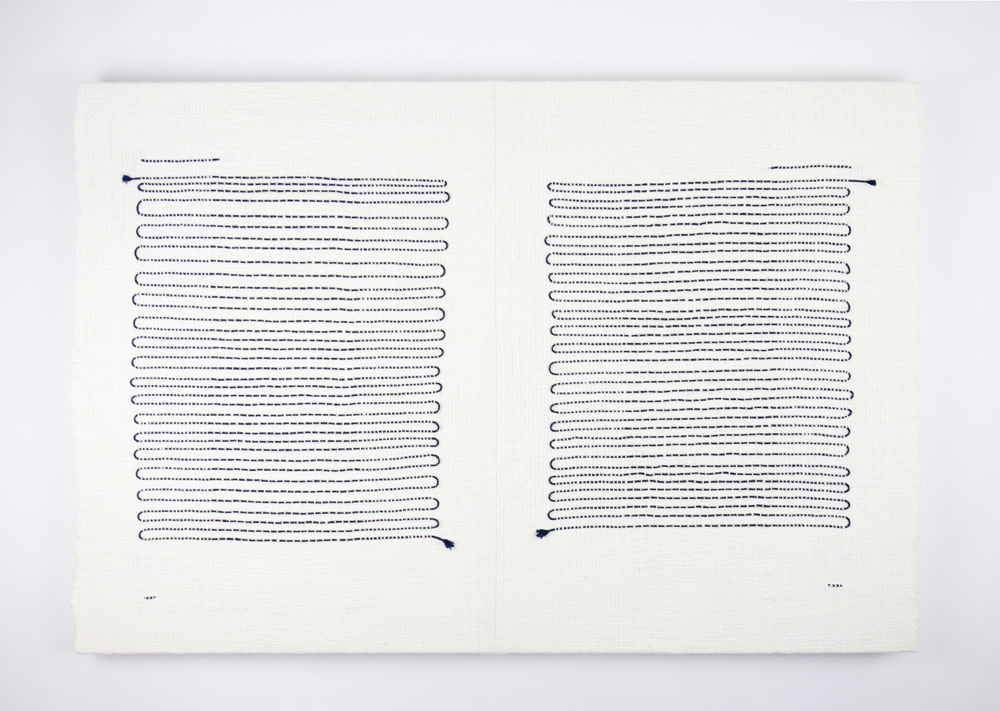

FC: I made two weavings inspired by the aesthetics of the written page in 2012 while I was at the Haystack residency, and then put those ideas aside until most recently. These two weavings were a jumping off point for my formal choices in Text means Tissue. In 2014, while I was working on Writing in Threads, I focused on generating a wide variety of woven forms, fibers and colors, since those weavings would then be "translated" by different writers. I tried to create aesthetic diversity for the written outcomes. So the work didn't really evolve in the way that the Text means Tissue work did, because I was always trying to make something completely different every time. With Text means Tissue, the intent was to create weavings with a similar process to how I might sit down to write something. I wanted to create the experience of being in front of an empty page, with just my mind, and whatever was passing through it. It's quite a meditative task. I'd start weaving a blank substrate (usually in a white, black, or ivory yarn—neutral or "blank" colors), and wait to see what passed through my mind, and then record it in the weaving. One formal objective I kept in mind while weaving was empathy, creating spaces for the eyes and mind to rest. The back and forth of the lines that appear in this work is inspired by boustrophedon, which is the form that western writing took before there were spaces and lines as we now know them—this occurred in Ancient Greek, among some other languages. Boustrophedon means "as the ox turns," and it is a natural conceptual and formal fit for the movement of a woven line.

Francesca Capone, There's a knot where I was picked pure (KM), 2017, cotton, metallic thread, reflective thread, and polyester rope on wood, 36 x 24"

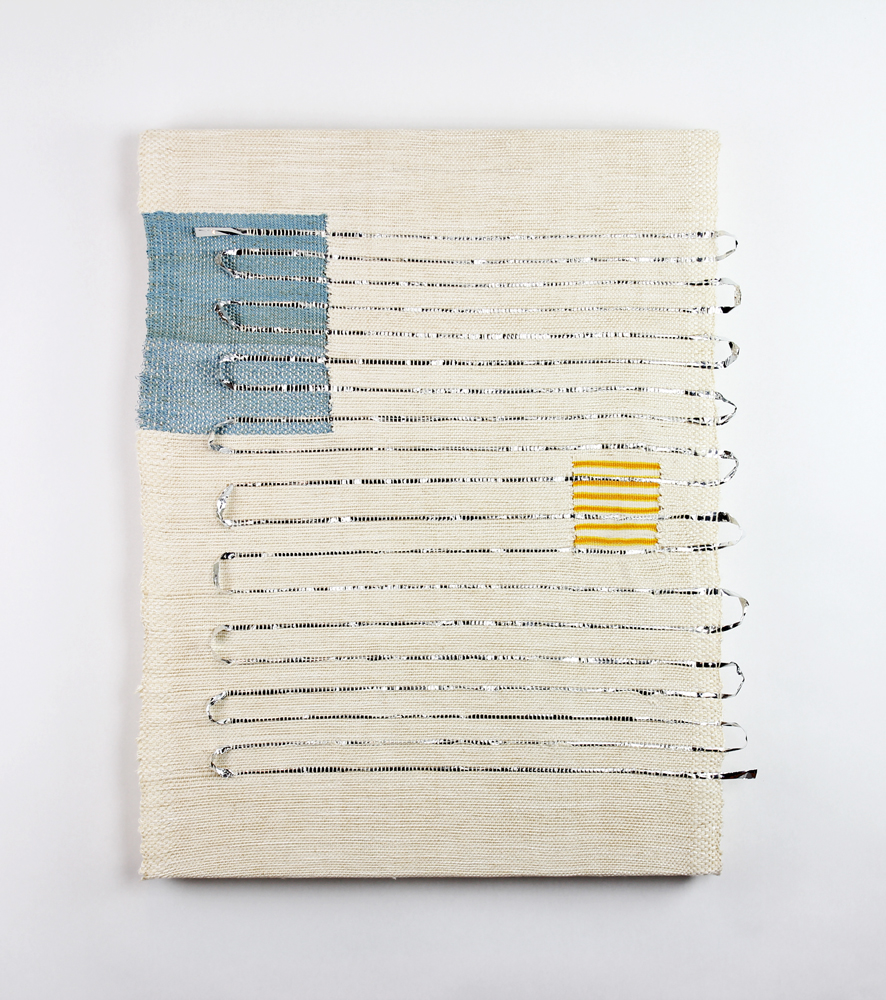

GLL: I love the material choices in these works. You go from super natural fiber, non-dyed cotton to very "futuristic" appearing materials—reflective thread, metallic cord, and Mylar. How did you come to combine these materials in your work?

FC: Material choices are a kind of vocabulary. Weaving can have a misconception of being an antiquated craft, but it's really just like any other medium—there's always new ways to reinvent it, and make it feel relevant for today. Through my commercial work in the textile industry, I'm exposed to the newest innovations in fibers as part of my day to day. Weaving with the materials that have come on the market more recently makes me feel connected to this moment in time. I especially love mixing old and new, and finding ways to integrate the futuristic stuff with other fibers that are tried and true, like wool and cotton. Our culture is all about new new new, but really it's impossible for all objects to be new—the new objects just layer onto the old, and I find this strange and fascinating.

Francesca Capone, I'm trying to tell you something about how rearranging words rearranges the universe (MH), 2016, cotton, reflective thread, and Mylar on wood, 24 x 18"

GLL: You have a chair in the exhibition that is a collaboration between you and furniture designer, LikeMindedObjects. For me, this piece is a reminder that textiles are often functional. Do you often make functional weavings? How do you think textiles change when given these different contexts and purposes?

FC: Though I have designed functional textiles, the chair is really the first that I've handwoven. There's something really special about it I think—and it was palpable through the whole process. My interest in making the chair was purely conceptual. I wanted to create a situation where the idea of a textile supporting a body was conveyed quite literally, since a big part of the show was exploring ways that textiles have supported the lives of women. I felt really connected to women's history as I was weaving it. I was reminded of women in antiquity, and I was humbled by the consideration that before the industrial revolution, there was a cotton industry of women in America who hand wove fabric for sheets, clothing, dresses, pants—everything. I wove fabric on an enormous AVL loom during a residency at A-Z West in Andrea Zittel's weaving studio, accompanied by two other weavers, Ricki Dwyer and Elena Yu. It took me three full workdays of non-stop weaving to make the fabric for the chair. I used a flyshuttle to efficiently weave 60 inches from selvedge to selvedge, a swinging the shuttle for every pick. Nowadays, nearly all fabrics are made by mechanical looms. It's easy to disregard labor when something is machine-made, making textile objects feel disposable, not at all precious. In contrast, it feels really special to sit in the chair, since it was woven with the same amount of care, time, and thoughtfulness as the weavings on the wall. I really hope that people feel connected to Elsie (LikeMindedObjects) and I when they sit on the chair, and I hope they feel supported.

Francesca Capone + LikeMindedObjects, I don't know how people have enough time, I feel like I am falling through mine (ML), 2016, cotton, glow in the dark cord, reflective thread, and metallic cord on bent steel, 41 x 41 x 32"

GLL: The notion of design and functional objects also reminds me of your day job as a textile designer at a large sportswear company. Can you talk about how these worlds collide in your daily life and studio practice?

FC: My studio practice and my commercial work are pretty separate, most of the time. As I mentioned before however, my awareness of contemporary material culture is heightened because of my commercial work, and this undoubtedly influences my palette of yarn choices. My studio practice is driven by my personal experience, my relationships with other poets and artists, and my conceptual interests in language and textile. In contrast, my commercial work really has nothing to do with me as an individual, aside from harnessing my ability to research, my taste in textile, and my technical knowledge—it's more about the consumer that I am designing for. It's almost like using two completely separate parts of my brain, and as time passes, it's become much easier for me to switch gears. I think the way that I use my hands really helps define my studio practice—I touch every thread of every weaving that I make and I push type around in InDesign to carefully make the book—it is all very slow-going, a lot of thoughtfulness and time goes into it. My commercial work takes great focus, but it happens in a fast paced, collaborative design environment, and then the fabrics are all machine made, so the processes and outcomes are significantly different. I think there's a lot to be learned from trying to distinguish this space between art and design, personal work and commercial work, and I find opportunities for intersections to be challenging and exciting. I think that is why the chair is my favorite piece in the show, it raises a lot of questions in this arena.

Installation image of Text means Tissue

GLL: This may sound a bit off topic, but I'm so curious about how you organize your time! You are so insanely productive and driven, working in many different arenas—weaving studio, book designing, writing, and working a demanding day job. How do you stay focused?

FC: I think for this show I might have pushed my multitasking to the limit! I was pretty reclusive for about 6 months, so I could get all the weaving and editing done. Really it comes down to awareness of the limited hours in the day, and attempting to divvy it all up into everything you want to do. It's exhausting to burn the candle at both ends, but I've been fortunate in that both ends of the candle are interesting to me, so it feels good. I think the desire to keep making keeps me focused.