We continue our artist interview series with represented artist William Matheson, who offers us here insights into his process and thinking behind his current series, Night Was Already in My Hands (on view through October 19).

William in his studio at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA

Gabi Lewton-Leopold: The title for this show is taken from a poem by the Japanese Modernist poet, Sagawa Chika. Can you speak about how the line in the poem came to be the title of the series? How do you feel it informs the work? It's interesting too, recently I was talking with Elizabeth Malaska about her titles, many of which come from poems, and she spoke about how she felt a kinship between poetry and painting; that both mediums can talk about our world and create their own in the same moment.

William Matheson: Poetry is one of those things that I only read occasionally, but every time I do it seems to directly enter into the paintings. I’d say more regularly I read novels, and of course, because I’m in grad school, there is always lots of art theory/contemporary art literature. But I always really relish the brief intervals of time that I spend with poetry, as it can provide a pretty rarefied form of inspiration. This has to be stated as a bit of a generalization, but I think poetry and painting share a certain type of resistance and opacity. Both can deal with a type of intimacy that can be hard to find in other mediums, something that exists halfway between reality and something else, something stranger. They’re both also rather precarious and slippery. I guess this definitely relates to the mixture that Elizabeth mentioned, of existing halfway between our world and another. There’s a great quote by Wallace Stevens where he says, “To a large extent, the problems of poets are the problems of painters, and poets must often turn to the literature of painting for a discussion of their own problems.” The two mediums have a long history together, they seem to have necessary overlaps in how they construct a space to interact with.

I just recently discovered Sagawa’s poems and I was just immediately taken. Her work seems to straddle this really interesting line between sensuality, in terms of how she describes details from nature, and this almost overwhelming sense of doom and angst derived from being human, from having to exist. There is also something very simple and refined to her work, which I deeply admire. I chose the last line of the poem because it tonally related to the paintings and what I wanted from them, and also because it’s the most ambiguous line in the work. “Night was already in my hand” exists on this interesting spectrum between unsettling—if we take the “in my hand” in the poem as a negative, almost like something subterranean or internally corrosive—and powerful, because it’s the first line in the poem of possession, of having control over what occurs. I wanted something of this kind of ambiguity to be present in the show, a struggle of sorts.

GLL: The poem paints a very bleak scene, and like the poem, there also seems to be a theme of darkness, or evening, cast over the paintings. Does this ring true to you?

WM: Darkness is such an interesting thing currently. I was just reading Jonathan Crary’s 24/7 last year, which is a book I have mixed feelings about, but one of the main topics is how night, as both a diurnal occurrence and a potential political/creative position, is being totally eradicated contemporaneously because it exists in opposition to capitalism. It’s something that cannot easily be utilized or monetized because it is essentially a space for inactivity and dreaming. I won’t make this a discussion or critique of capitalism, because I don’t think that’s what this body of paintings is about or is trying to achieve. But this idea that Crary outlines, the possibility of the end of night by light pollution, the end of sleep from advancements in drugs, even the end of the dreamer, I think it’s really charged.

I’ve always been quite night oriented in my rhythms and lately, I’ve found night to actually be a fairly crucial position for me in my work, rather than just the time and space when I’d create and think most fruitfully. Night and darkness entail a sort of resistance, an embodiment of the mercurial. I like that night is readily associated with returns: the return of the past, the return of the dead, the return of deep subconscious emotions, of things unseen and unexplainable. It has an uncanniness or unpredictability to it. So, I think that’s where a lot of these paintings come from, or what I was thinking of while making them. Many of the works are populated with specters and other embodiments of this sort, like the hazy figures in Autumn at the Feet, or the wobbly dreamer from Afternoon or the feet and lemon in Self Portrait with Lemon.

Afternoon, 2015, oil acrylic, and dye on canvas, 26 x 18"

I had a great studio visit with the artist Keith Mayerson recently where he brought up Foucault’s idea of the panopticon in relation to everything I was just talking about. The panopticon is a type of centralized prison arrangement that is designed for constant surveillance, where no one can tell when he or she is in fact being surveyed. Basically it’s a system that runs on uninterrupted visibility, of constant watchfulness and light. If we think of night, creatively, politically, socially and metaphorically as a way of subverting being seen and surveyed contemporaneously, of retaining the position of being dreamers in some way, well I think that’s great, and that’s a position that I want to be present in the work, even if it may be very quiet or indirect.

GLL: While I've definitely thought of sleep as an unpredictable and maybe even sacred space, separate from the waking world, I've never thought of it as a political space. I'm wondering how you see protest entering into the discussion. I think this idea of quiet moments and spaces is especially relevant and important in today's world where we are constantly confronted with modes of communication and distraction during our waking lives. It is only in sleep and moments of great self-discipline (say in the studio or meditation) that we can get away from it all.

WM: I think that there is, or can be, a protest aspect to painting—of indulging in what could be seen as a sort of dream manifested formally, something far removed from what is demanded currently of people. Painting has an odd temporality to it still, with all of its ancestral connotations. So, I think that time spent on painting in the studio (this could easily extend to other mediums in different ways) is a bit like sleeping, going inwards and trying to resist in some way or another.

It makes sense that we're so embattled with sleep and inactivity, because on an evolutionary level it's so ridiculously vulnerable. For example, if you went back 50,000 years, sleeping may well have been one of the most dangerous and easily preyed upon parts of our existence. So, on a biological level, we may feel hostility to this time and space that entails complete lack of control. But I think highlighting this vulnerability, retaining it, and being honest about the fear that lack of control brings is very important too, especially for the arts. And this can definitely entail resistance.

I also don't want to sound like a lamenting culture critic here, because contemporary life is far too complex to simply wring your hands at, and many of the things I'm alluding to come with enormous benefits. But it's getting harder and harder to approach this state of being in 'night', with computers and cellphones demanding time in both the studio and all throughout the night, and to find some sort of actual 'darkness' in all of its varied connotations, with growing light pollution.

GLL: Your previous show at Nationale, Sunless, also featured ghostly, hollow-eyed figures but there seemed to be more of an interest in landscape with that series; perhaps a more horizontal use of space, where as this show is more vertical. What has changed in your thinking and practice between these two series?

Skull In the River, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24", Private Collection (Portland, OR)

WM: Sunless was definitely a more representational/colorful/poppy show than Night Was Already in My Hands. I think of the paintings in the current show are more internal and abstract, both formally and in other less describable ways, than Sunless was as a whole. If I remember correctly, I was trying to imbue many of the paintings from the previous show with a digital quality. Many of them were appropriated from online sources—video games, screensavers, things of that ilk, so the paintings held onto some of that odd, hyper colorful, verging on absurd energy that was in the references. I think this kind of determined the landscape quality as well: the images that the paintings were derived from maintained that format.

The works in Night Was Already in My Hands are for the most part not taken from direct sources, so that may explain a bit of the shift from horizontal to vertical. Also verticality is typically associated with the portrait, which has more intimate, internal connotations. I definitely think that this body of paintings, compared to the last, has a more introspective, quiet goal.

GLL: The paintings in this show are either on pre-dyed colored canvases, or on canvases that you dyed yourself. What attracts you to working in this way? When you start with a colored canvas, does it act as a welcome restrain/frame, giving you some parameters in which to work?

WM: Like many painters, working with different surfaces/restrictions/presentations can be really rewarding for me. The usage of pre-dyed to self-dyed canvas definitely becomes an avenue for containing and potentially constraining the content. I think the pre-dyed colored canvas comes from wanting to engage with flatness in a very direct way, to create a very literal tension between the painted sectioned and the pre-dyed section. These works become a bit like an image on a screen or an illustration in a book. They don’t have complete autonomy in the same way that a more fully rendered/completed painting would.

With paintings like WK (the Architect’s House) or Afternoon, where I dye and paint the initial layer, I’m looking for different type of conflict. These surfaces read less like a book or screen and more like something organically growing or decaying over time. These paintings are darker too, and I think relate to the mercurial aspect of night that I previously mentioned. Part of that comes from materials used; in WK, the lighter stained areas arise from bleach and water poured onto the dyed surface, and in Afternoon, some of the hazier areas are created by spraying a very watery mixture of paint and dye through an airbrush.

Throughout many of the paintings there’s an attention to space, and especially compartmentalizing the space in which the painting realities exist. So both the self-dyed and pre-dyed canvases become a way to navigate different versions of this.

WK (the Architects House), 2015, oil, acrylic, dye, and bleach on canvas, 41 x 33"

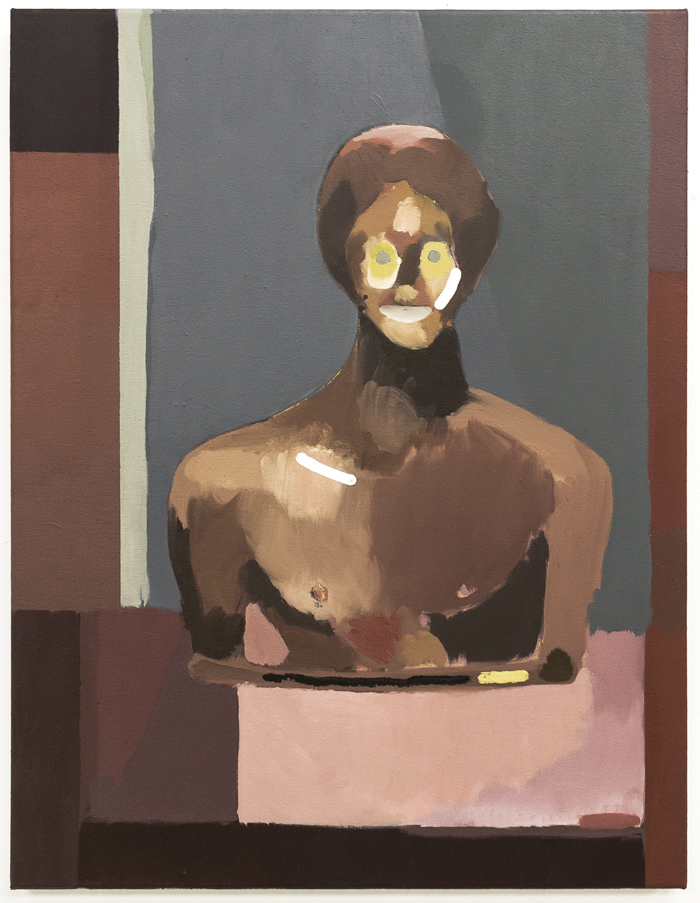

GLL: There is, for a lack of a better phrase, a signature mark that is repeated throughout your work. It's an arch of solid color, for this series it is done in white. At times, it seems to be used as a highlight, say on the collarbone and cheek bone of the figure in Smiling Etruscan Bust, other times as in Autumn at the Feet, it serves as a pause, a comma, that interrupts the color field. What's your thinking behind this mark?

Smiling Etruscan Bust, 2015, oil on canvas, 26 x 20"

WM: I see the arch as a sort of personal signature to be sure. It originated a couple of years ago, while I was at a residency at the Vermont Studio Center. I had made a semi-grey, blurry painting of two polar bears fighting, which was starting to have nods to some of Richter’s blurred paintings, and I started thinking what I could do to upset the mood that was becoming prevalent in the image, because it wasn’t working, or it felt derivative. So, I placed this bright blue poppy arch right between the two bears, and it seemed really funny, and changed the tone of the painting quite substantially. In retrospect it oddly allowed it to contain more conflict.

Two Bears Fighting on Thinning Ice, 2013, oil on canvas, 24 x 32”

Since then it’s become a way to upset what could become heavy handed paintings, like Autumn at the Feet, or a way to add movement and rhythm in other works, like Smiling Etruscan Bust. The arch has something of a spatial quality, a bit like a miniature entrance, but it is never large enough, or rendered enough to be complete. I always hope there’s a certain sort of tension to it, halfway between something cartoonish and something more mysterious.

It’s usually made by squeezing the paint tube right out onto the canvas. I suppose in this manner there are also ties to certain forms of digital painting in the mark, I’ve always felt that it has a sort of digital register in its application, as it can appear a bit like something made in Photoshop or Illustrator. Sometimes I over do it and put too many arch-like paint lines in the works, and those ones can start to feel gimmicky. But if used moderately, it can become an interesting tool to break the space and mood up in strange ways, to add another dimension.

GLL: Can you tell us about your consistent interest in mythology and references to figures from antiquity?

WM: I find myself constantly turning to ancient references because of the interesting mixture of art historical canonization and uncanniness that exists within their parameters. Almost any art history course covers the myths, artworks and artifacts of the Etruscan, Grecian, and Roman periods; the images they produced come as close to being foundational human images as any, at times seeming like universal embodiments of creativity/humanity. They’re so loaded.

But, like a mask, or a doll, these ancient busts and sculptures are inanimate and have a certain vacancy to them, a long, somewhat inaccessible material history. I was just reading a short interview with the artist Carrie Moyer and the way she describes her attraction to ancient busts, masks, and armor is really well put. She says it exists as a search for “forms that were nearly recognizable…that generated a preliterate force.”

So, I think it’s that odd balance between familiarity and something inherently removed that continually attracts me to them.

GLL: There are two paintings in your current show, one titled Country Witch and the other, City Witch. The latter is very abstract with solid blocks of blue, black, gray and yellow, while Country Witch is much more figurative—it depicts a face made of differing tones of blue. What is the significance of the witch? What does that figure mean to you within this series and do you see the major differences between these two witches as meaningful?

City Witch, 2015, oil on canvas, 25 x 20” and Country Witch, 2015, oil on canvas, 22 x 18”, Private Collection (Portland, OR)

WM: The Witch, like the bust or the doll, is such a fascinating character because there’s something inherently archaic, or old fashioned to her. Like I previously mentioned, there’s a certain uncanniness to these figures, a vacancy, so to speak. They’re figures/beings that are not animated or real, but they still have a deep psychological resonance and an eeriness/romance for lack of better words.

There’s a great drawing that I often think of by the early 20th century outsider artist August Natterer called Hexenkopf. In the work, the boundaries and perimeters of a quaint Grandma Moses-esque town comes to form the head of a giant, grinning witch's head. As a drawing it’s both funny/playful and simultaneously deeply disturbing. If I remember correctly, the drawing was created right before the beginning of World War I, and the act of casting the witch, a pagan figure, as the embodiment paranoia of what was a fairly industrial/mechanistic age is really interesting. Like, how can the witch possibly be used to address contemporary uncertainty or fear then and especially now? There’s almost something futile about the character. Also, there are of course the kitschy Halloween associations (I’ve actually made some small witch paintings based directly on cheap costume masks), and the disturbing narrative of the persecution of otherness. They’re creatures of the night too, like any character with horror associations, which ties into everything else. I guess I’m attracted to the witch because she represents an odd combination of elements, something halfway between a kitschy joke and something more tragic.

August Natterer, Hexenkopf (The Witch's Head), 1915

The titles, funnily enough, actually come from that old children’s story, The City Mouse and the Country Mouse. I think the story goes that each mouse visits the other in their respective homes, and the country mouse can’t understand or adjust to the city, and in the city mouse’s case, the country. I think I really just liked using that narrative reference for the titles because it’s a bit of joke, but actually it does make sense that the city witch would be more alive and simultaneously fractured.

GLL: Who are some of the artists you think about often? What have they taught you?

WM: Always a fun question. I guess these would be the artists/filmmakers/writers I think about/am inspired by now, in no particular order: Peter Doig, Michael Armitage, Marcel Desgrandchamps, Ted Gahl, Victor Man, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Clarice Lispector, Jose Donoso, W.G. Sebald, Roberto Bolano, Carl Dreyer, Chris Marker, Laure Prouvost, Jon Rafman, Rachel Rose. God and I feel like I’m definitely leaving people out.

I don’t know if I can neatly summarize what these particular artists have taught me though. I’d probably need to type page after page for that, which would inevitably become a bit of a ramble.

GLL: What's next for you in the studio?

WM: Actually, most of what I've been working on currently has taken place in video. I've been wanting to make film/video work for years now, and going in to my second year in grad school, with access to great resources and the input of my peers and professors, well, it just felt like the exact right time to push myself to find new ways of conveying my interests.

This obviously doesn't mean that I'm going to stop painting, but for the next several months I'd love to find new ways of dealing with all of the themes that are percolating here in this show: night, returns, dissolutions, specters. It's been both daunting and extremely exciting and rewarding.