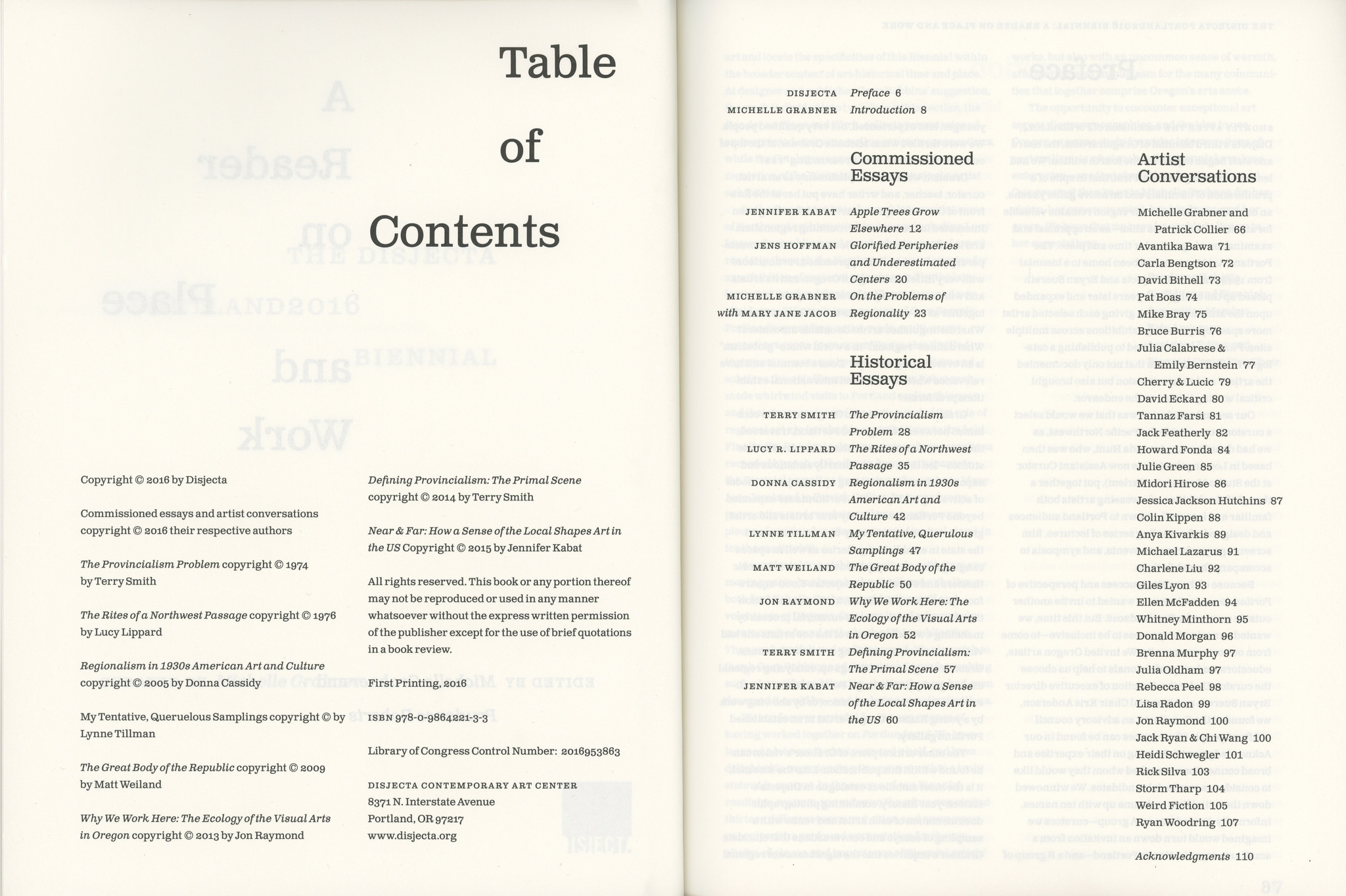

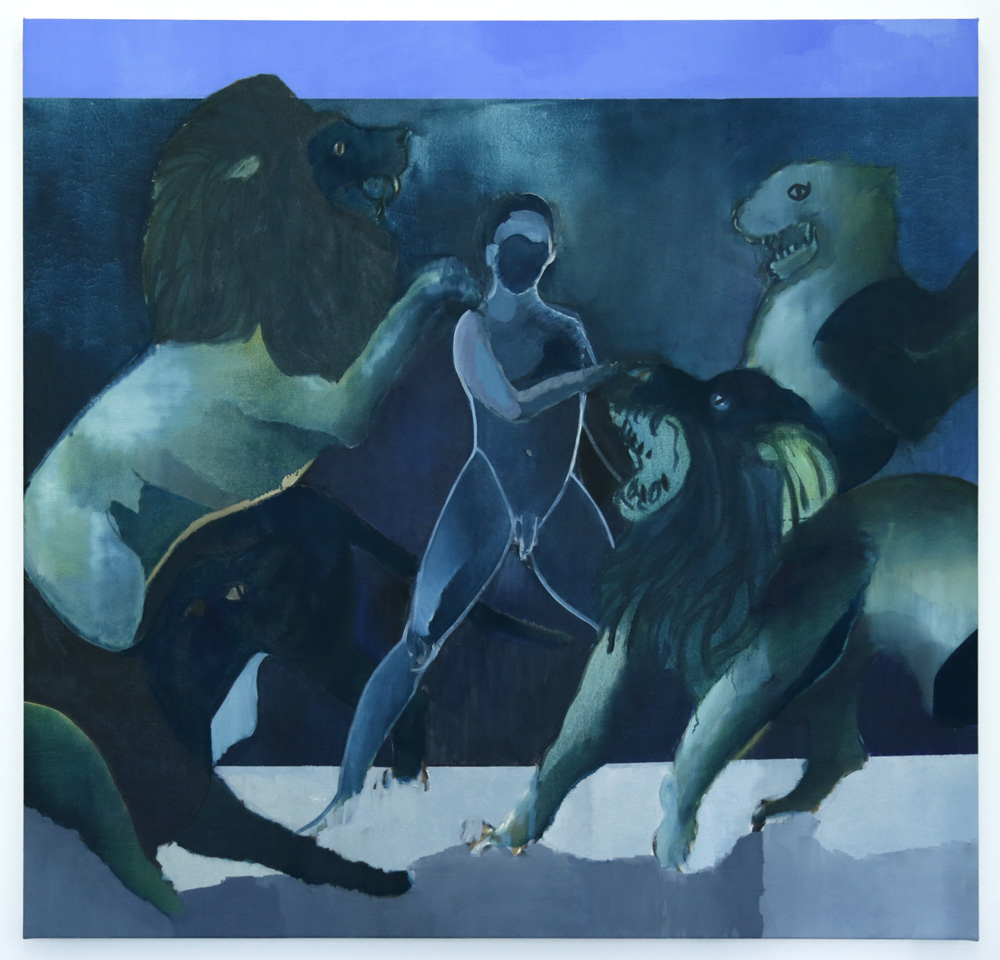

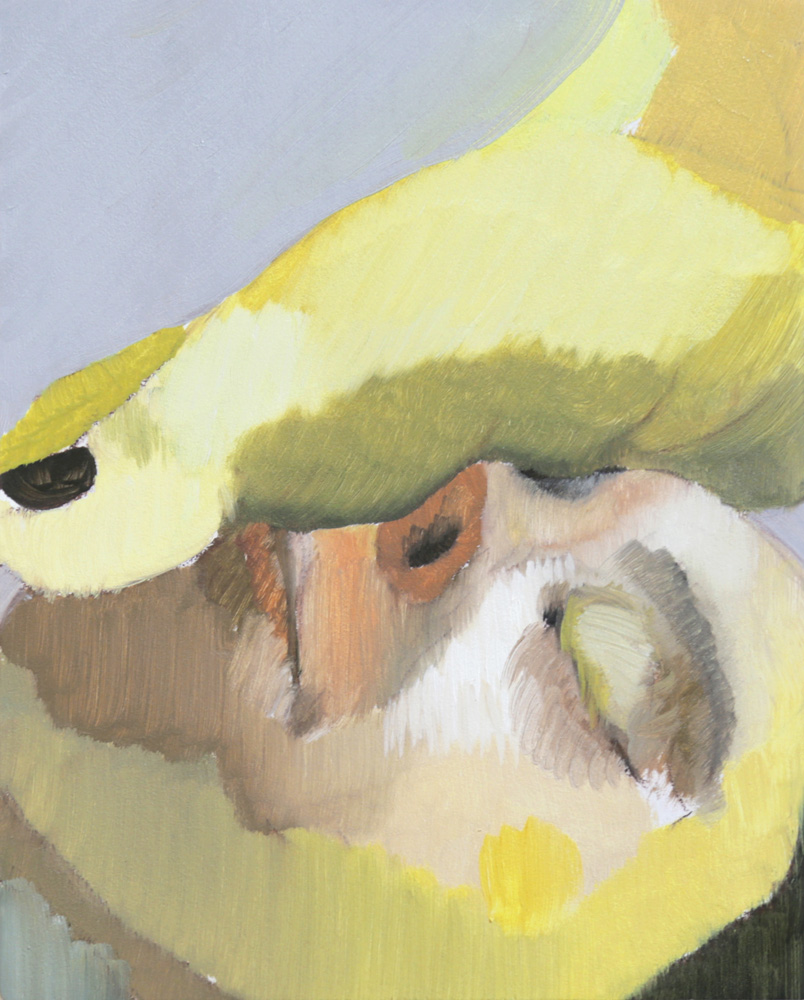

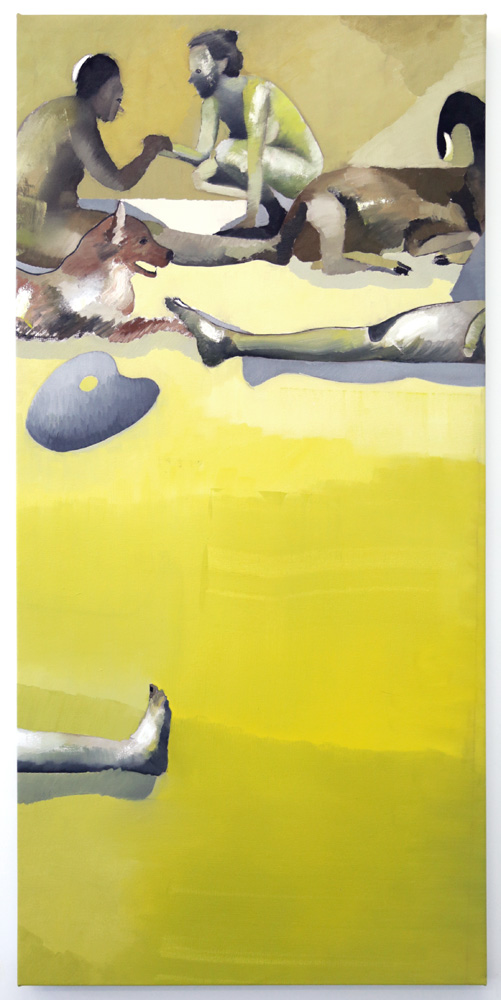

Nationale proudly presents a flash exhibition of Emily Counts’s newest work, as well as a special musical event: Party Store performs with Super Mode!

Super Mode is an interactive sound sculpture by Emily Counts recently shown as part of Sonic Arcade at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City. It consists of a walnut wood box topped with ceramic objects that trigger individual sound samples when pressed downward. Illuminated windows in Super Mode allow the user to view the interior mechanics and wiring of this piece. Programming and circuitry design by Andy Myers and sound samples by Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe.

Emily Counts was born in Seattle, WA, where she currently lives and works. She studied at the Hochschule der Kunste in Berlin and the California College of the Arts, where she received her BFA. Her work has been exhibited in Portland, OR, at Nationale, Carl & Sloan, and Disject; in New York at the Museum of Arts and Design; in Tokyo at Eitoeiko and Gallery Lara; and in California at the Torrance Art Museum, Garboushian Gallery, and Mark Moore Gallery. Counts was an artist in residence creating work for associated solo exhibitions at Raid Projects in Los Angeles and Plane Space in New York. She has received grants from the Oregon Arts Commission, the Regional Arts & Culture Council, and The Ford Family Foundation. She is a member of SOIL Gallery in Seattle, WA, and is represented by Nationale in Portland, OR. / IG @emilyraecounts

Party Store is a lo-fi ambient project by Seattle musician Josh Machniak.

On view: April 21–April 22, 2018

Opening reception: Saturday, April 21 (6–8 p.m.) with a 20 mins performance at 7 p.m.